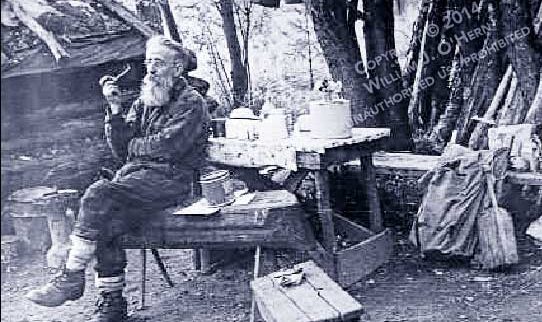

Corn bread “muffins” as Noah referred to them were standard fare at Cold River during the colder months.

The hermit cooked over a “kitchen range” that was an old 55-gallon oil drum cut in half lengthwise with a flat heavy steel top as a cooking surface. In the beginning, Noah’s “oven” was nothing more than old food cans. He would pour the batter into the 3038 containers. He had collected enough different sizes of cans for his makeshift ovens to bake several tin-sized loaves for several people if they happened to be in camp. To retain the heat, he placed an inverted larger can over the open top of the smaller can. Next, he placed an even larger can over the two smaller cans. The larger can that covered the two smaller ones captured the heat from the stove top and baked the contents perfectly. The only drawback was he could only produce a few loaves at a time. Of course, if there were many at camp, after the first cans were unloaded they would be re-greased, refilled and were ready to be eaten by the time the first batch was consumed. It took time, but time was plentiful at camp.

After 1943, Noah used a reflector oven. It was given to him by Dr. C. V. Latimer Sr. Noah referred to it as his “Ace Woodsman” because Doc Latimer had punched that name into the metal top with a nail and hammer before presenting the stove as a gift. Noah enjoyed the small stove-top oven. He baked sourdough biscuits and potatoes in it the first evening. The small heat indicator in the door never failed to steam over on the outside. When they joined forces during the trapping season, Noah told Smith it was his job to wipe the condensation away with a cloth so the rising dial could be watched. “The breadstuffs Noah baked,” Smith remembered, “were perfect complements to our meals. I always packed in jars of jams and jellies. The sweetness tasted es- pecially good back there in the woods.”

In Smith’s later years Richard always used the Quaker® brand yellow corn meal recipe listed below. Old-timers fixed corn meal with salt and hot water or milk, often adding maple syrup, honey or sugar to sweeten the mix. The blend was then fried in a greased skillet. Johnny Cake provided a filling meal in the bush. Southerners call it Hoecake.

In 1952, when Marjorie L. Porter interviewed Adirondack native Abram Kilburn from Wilmington, he related a curious true story involving Johnny Cake. Ira Keese lived his adult life in the mountainous Wilmington region. Ira made his living going around much like old time tinkers. He was a poor man. He lived with families he found employment with and made a living by hiring out his services. Abram Kilburn remembers Ira chopped wood and “did sapping” [worked in the maple sugar bush] in the spring. When he got so old and sickly that he couldn’t work and take care of himself, Abram took him in and cared for the sickening man.

“One day,” Abram said, “Ira wanted Johnny Cake. I said, “Yes, I can make that. So, I went and mixed some up and he et it and you know within an hour he was dead.” Ira said he went to Wilmington to get some help, telling whoever he called on that his Johnny Cake had killed old Ira, “so I want you to come up and help me box him up.” Abram pointed out that in those days “if you could get a casket at all they’d only be five and a half feet long.” Ira was six feet six inches tall. “So,” Abram continued, “Ira’s feet stuck out over the end of the casket by twelve inches!”

The men talked about what they could do. One fellow told Abram to go get him a hand saw. He pulled the legs up over the casket and sawed them off,” putting the remaining parts into the box. The teller emphasized to Marjorie that this was a true story. And, just to prove it he listed off the other men who were there that witnessed the bizarre event.