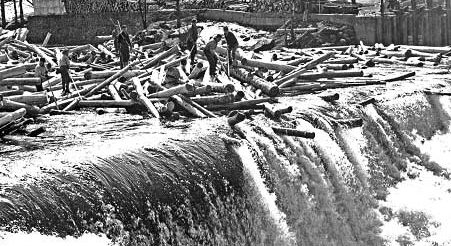

The “warp and woof” of old-time river drives has long since ended. A logger named John Shields remembered his river driving career in a 1916 interview when he recalled the “good old days.” His memories of those times and those river drives invoked the romance of past logging days. Shields said, “It was always a grand sight to see those big pine logs, with the bright sunshine on them, floating downstream.”

A Look Back In Time

The “warp and woof” of log drives

An article printed in “The Northern Logger “, Jan. 2022

The “warp and woof” of old-time river drives has long since ended. A logger named John Shields remembered his river driving career in a 1916 interview when he recalled the “good old days.” His memories of those times and those river drives invoked the romance of past logging days. Shields said, “It was always a grand sight to see those big pine logs, with the bright sunshine on them, floating downstream.”

Shields once drove logs down rivers and creeks in western New York, but his experiences mirror those of other river drivers throughout the state and nation. Older river drivers were fond of recalling their former big river log drives. Often the work was a family affair. Shields’s brother was also employed in the logging industry. Said Shields, “My brother Jim first worked with the crew; then Jim went ahead as boss over some men who broke the log jams. I stayed behind with a crew whose duty it was to see that all stray logs that had lodged on the banks were rolled into the stream and restarted on their way down the creek. Sometimes the logs were backed up so far that a team [of horses] would have to haul them back to the bank.”

At one time, river driving was the easiest and quickest means of transporting logs. This did not mean by barge, boat or log rafts, but by actually floating single logs with the current downstream from forest to mill. Log drives were exciting and dangerous aspects of logging. They were the last of what was once a common logging practice dating back to Colonial days.

The log drive was a regular feature for several generations, and there are many photographs of log drives after the advent of modern photography, both still and motion. Some of the latter days of the event were captured by a few novices, such as the Rev. Frank A. Reed, who used a 16-mm movie camera. Log drives were marked by accidents as well as successes, and were among the most picturesque events in logging history.

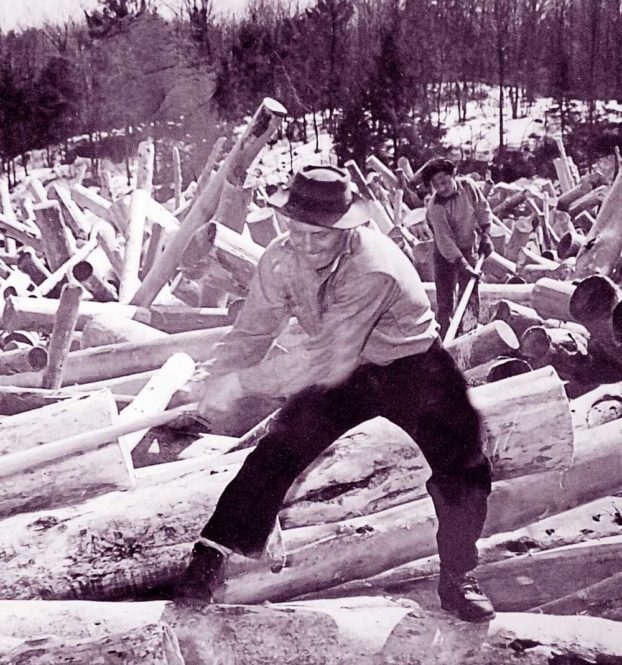

For several generations now, people have known about log drives and log jams only as legend. And although we rush to absorb the latest technological advances, our lives are less rich in that we will never witness first-hand one of the great dramas Log drivers of American industry. Log drives demanded crews of great skill, courage and daring as well as men who were nimble and quick of foot. And as great flows of logs sped down the rivers, the spectacle attracted crowds of curious spectators who cheered with hurrahs and hoots.

Kay Halloran and Eileen MacKinnon told me similar stories in 2005 of their father’s work as a log driver. Their father was Alexander “Sandy” Currie. Halloran said, “He left home at 14 to work on the log drives and did it for 15 years.” Currie’s log driving work came to an end after he met his wife in a boarding house following a river drive. After they married, his wife insisted he end participating on the log drives. The sisters believed their father had “a rugged life in his youth.” MacKinnon painted a picture of their father as a man with huge hands, “probably from working on the river.”

Halloran said that because of Currie’s expertise in working with dynamite, a skill he learned while on the log drives, he was called on “all throughout New England, from Maine and into New York State, wherever coffer dams were being built for paper mills.” He helped build bridges and abutments and helped direct sand bagging during the flood of 1936, when he was a foreman in the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression.

All winter, lumberjacks felled trees and stacked the logs in high stacks called “decks” sometimes 20 to 50 feet high on frozen rivers and on the edges of streams. When the river hit just the right stage – high and still rising slightly in the spring, the decks were dumped into the rushing water. Luck was never really with the drivers. The downriver journey of logs was never without incident. Perhaps a river dropped too sharply, and giant log jams formed on river islands, along the shore and against bridge pilings. There were pitches, rips and falls – all of which added to the ever-present danger of keeping the “sticks” moving down the rushing and sometimes angry water. Dynamite was often the loggers’ only weapon in breaking a log jam. Some men worked from bateaus to pull logs from eddies. Others used peaveys and pike poles, working from floating logs and boats that went up and down the river.

In the early days, a majority of logs went to sawmills along rivers. Later on, major log drives throughout the Northeastern states provided the wood used in making pulp for paper. And in time the indispensable tools – long pike poles, peaveys or cantdogs, and river driving boats that shepherded logs downstream – were replaced by the chainsaw, the truck and the log chain. In turn, river drivers became truck drivers. Automation and mechanization have now taken over every segment of American life. The warp and woof of early log drives is now only a romantic memory of old-time logging days. Log driving was a victim of mechanization, truck and rail transportation – all of which could do the job more economically.

Log drivers Willie Snyder and Charles Auston knew they needed to ride logs and handle pike poles and peaveys skillfully – or quit. There was no in between. White water men couldn’t wise crack themselves out of a jam and no alibi would save their life if they had to “ride her.”

PHOTOS COURTESY LYONS FALLS HISTORY ASSOCIATION

I wanted to hear tales about this river driver and landing foreman for the Gould Paper Company, a man with a reputation for toughness and hard work in hard conditions.

A Look Back In Time

My River Driver Father’s Career

An article printed in “The Northern Logger “, Dec. 2021

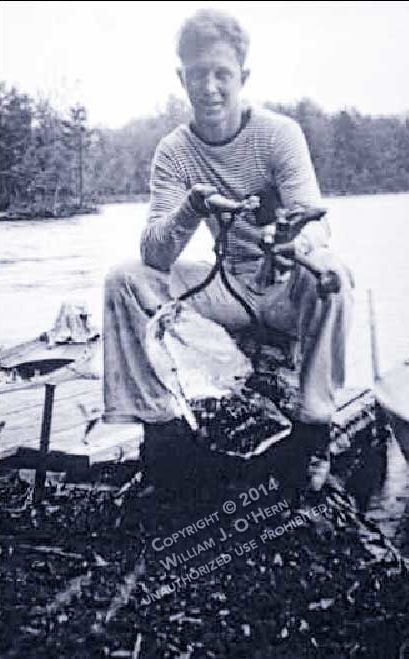

“Dad was one of the old-timers,” said Bill McGee on an early winter day in 2016. I spoke with him and his wife, Emily, at their New York home about Bill’s legendary lumberjack father, Herbert McGee. Herb was among those towering men who earned the reputation of “having the bark on.” I wanted to hear tales about this river-driver and landing foreman for the Gould Paper Company, a man with a reputation for toughness and hard work in hard conditions.

As stories go, when the old drivers were paid off at the end of a season most of them took to drinking and kept it up until their money was gone. They visited saloons with crowds, and their excursions often wound up in fights. The antagonists took sides, and pitched battles ensued, which sometimes continued for two or three days or until police arrived and the most belligerent of the drivers were taken to jail. On the other hand, many drivers who were thoroughly respectable citizens, as provident as men who labored in other, less hazardous fields. Herb McGee was a colorful character and the McGee family has some interesting history, including Herbert’s rum-running days and incarceration. “Dad did time,” said Bill, handing me a long newspaper account of his father’s arrest, and his mother Anna’s moonshine-making career during the days of Prohibition.

Herb McGee knew New York’s Moose River as well as any man. The river had first been used for log drives in 1851. River drivers knew the dangerous stretch was perilous. Men were crushed under the swiftly moving logs, chilled to death in the icy waters, drowned or otherwise killed trying to break up the great jams that formed at obstructions in the river. “Dad faced death each time he got on the river,” Bill continued. “A log drive was full of danger. He faced bobbing logs and rocks, biting wind, hail, sleet, snow, and rain in the spring. “Dad never wore mittens even though the weather oftentimes dropped to 50 below zero,” remembered Bill.

Herb hailed from East Bathhurst, New Brunswick, Canada, and began working in the lumber business at the age of 15 when he drove horses for a Canadian sawmill called the Snowball Company. “Dad came to Tupper Lake, NY, in 1913; he worked in the woods around Newcomb as a logger and loader for a private contractor named Ken Hunter.” McGee Sr. spent over 50 years in the logging business and worked for the Gould Paper Company (Georgia-Pacific) for 30 of those years. Over the years, McGee had related many a fact and a yarn or two to his sons, Bill and Herb Jr., about his experiences in the logging and lumber business.

T.C. Williams’ gas Lombard at Gould Lumber Camp 7.

COURTESY FRED WORDEN

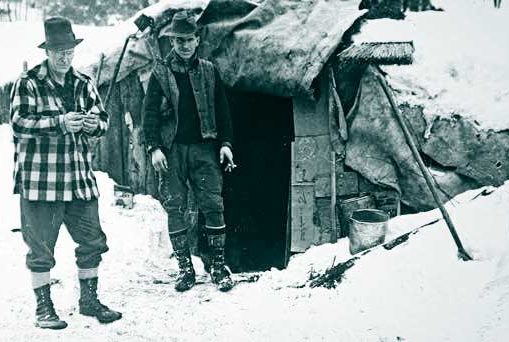

During the fall and winter months, Gould’s river drivers spent their days in the lumber camps. Bill described the typical camp as simply a long log building, usually consisting of a cook room at one end, an area in the middle called the “dingle” for unloading supplies, and the sleeping-living area, called “the men’s room.” The men’s area was one room with bunks lining the sides. Bill recalled his dad saying, “Many a yarn was cut in those days around the center heating stove before lights went out.”

Herb related that the food was great, they had plenty, and it was always homemade. His camp only had one cook, and that was his only job. Sometimes the cook chose ‘chore boys’ who helped with different jobs around the camp. Work throughout the winter involved cutting, hauling and stacking logs on the frozen half-mile-long stretch of river known as The Landing. Gould’s main landing was on the south branch of the Moose River, located a half mile below Gould’s Camp 9. The location was (and still is) on the property of the Adirondack League Club.

At the time of ice break-ups, the men gathered under various bosses to prepare for the drive. Herb knew some drive bosses who were “scarred and rheumatic from frequent exposures to wind and water.” Stout, flat-bottomed Moose River boats were prepared. Experienced men were equipped with iron-pointed pike poles which they used to free the all-too-numerous log jams that piled up on the journey to the mill. Whoops and yells, jokes and laughter were a part of the daily task. Some of the river drivers wore heavy woolen underwear, so thick they could stand a five-minute bath in the icy waters without suffering ill effects.

McGee, as the big river boss, was the key man. It was his responsibility to search out the log responsible for a jam. Sometimes it was necessary to attach a rope to it. A crew of men would then attempt to pull it free. Sometimes they needed dynamite to loosen a jam. This was the most dangerous job, since the jam might be freed by mounting water pressure while the dynamite was being placed. If the river driver was caught in the jumbled mass of moving logs, it would mean almost certain death.

Herb McGee retired from the Gould Paper Company in 1949, two years after the company’s last river drive. The days of river driving were over and McGee’s career was at its close.

When I visited Bill, he showed me some pictures. One colored snapshot was of Herb and his good friend “Huey” Dowling, dated 1964. “Dowling was known as a ‘Walking Boss,’” said Bill. Hugh was in charge over all of the camps of the Gould Paper Company. The lines in the older men’s faces tell some of their hard-bitten stories. Fortunately, filmed and taped interviews, camera-savvy photographers and personal memories have kept a permanent record of McGee and other men “with bark.”

As I looked at a 1974 photo of eighty-year-old Herb clutching a double-bitted axe and posed in front of a huge pile of firewood he was splitting, I couldn’t help but wonder: What kept a river driver on the job? Romance? The neverfailing lure of the white water? The dark bobbing logs? The crazy laugh of loons on the lakes? Perhaps the throaty song of the camp cook or the unique taste of his floury dough bread? There must have been something that kept calling the river driver back to his thrilling, exciting, dangerous life. Herb was but one of a race of hale and hearty, rough and ready men. His work is like a noted homegrown tobacco: “it will kill or cure” as an old saying goes.saying goes.

Herb McGee early 1940s on the Moose River.

COURTESY LYONS FALLS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION

Tug Hill Storytelling: Visualize how America’s Great Northern Forest would have appeared if seen from above in 1820, stretching from Minnesota to Maine.

A Look Back In Time

An article printed in “The Northern Logger “,Nov. 2021

Visualize how America’s Great Northern Forest would have appeared if seen from above in 1820, stretching from Minnesota to Maine. Imagine a sea of continuous forests comprised of a mix of softwood and hardwood trees: Miles

upon miles of spruce, balsam, pine, birch, maple, beech, cherry, oak, chestnut, and other tree species spread across a great expanse.

Twenty years later, pioneer families that immigrated to America pushed westward from New England, where small towns had grown to metropolises. “Long lines of people had been coming into the country as the result in part of the 1848 revolutions in Europe,” explains Tug Hill author Thomas C. O’Donnell. “Europe was demanding more and more American grain, the Central States were producing untold quantities of it, and labor was being imported from Europe

to build railroads and ships to carry the produce.” Once wilderness, the character of the land was changing from farmland to booming cities. O’Donnell continues, “Homes had to be built to house the new populations, and harbors and docks for accommodating the ships. America was fast becoming industrialized and one of the industries

that matured over night was lumber.” With so many office buildings, factories, wagon-and barrel-making shops, docks,

shipyards, and so many other businesses being built, wood was in high demand.

By 1850, logging companies were actively harvesting America’s forests from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic seaboard.

Equipped with double bitted axes and crosscut saws, lumberjacks felled trees and skidded logs with horses

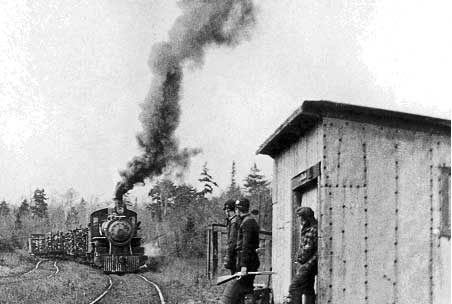

to rivers and floating the logs to mills. Twenty years later, logging companies that cut hardwood trees – trees too heavy to float on rivers – loaded them onto flat cars and transported them to sawmills by train.

As logging diminished the virgin forests, concern for protecting and preserving vital forests for future generations emerged among the public. Scientific studies, often from Europe, in the new field of silviculture advanced woodland knowledge. Foresters, trained professionals who studied what we today call forest sustainability, appeared on the

scene. Loggers became educated and imparted their knowledge to other loggers. No one wanted to see forest

land disappear, nor did they want a way of life to come to an end.

I enjoy listening to older loggers talk about their careers in the woods. Some of their tales about their experiences can create a lot of nostalgia. Learning about the evolution from old-style logging to mechanized methods is a reminder of the advancements in technology seemingly realized in a short period of time. There have been stories that made me laugh and others that amazed me, but the true stories of averting danger and death are reminders of how dangerous the job could be in the old days of logging and even today.

The Adirondack logging careers of those I’ve spoken with and heard about have been an eclectic mix: forester, cook and cookie (a cook’s assistant), teamster, mechanic, Linn tractor driver, camp clerk, blacksmith, truck driver, chopper, notcher, spudder, road monkey, swamper, straw boss, river driver, dynamite expert, cat skinner, whistle punk.…A complete list would be as long as a pike pole. Most often, the drama of an Adirondack log drive relived decades after still dwells within the heart of a lumberman, and for the outsider is a reminder that log driving was serious business. Today’s loggers and sawmill workers are contemporary business owners and workers in a global industry. The industry includes workers who do everything from haul logs from the forest to produce paper, furniture, baseball bats, and countless other wooden items.

Logging has moved into the 21st century, but the memory of an earlier time remains – the time of lumberjacks and lumber camps. While the colorful old-style ’jacks, fiercely proud teamsters, inventive blacksmiths, prima-donna cooks, log-hopping whitewater men and river hogs have passed on, logging goes forward. Meanwhile, their history continues to draw attention to their times.

The history is particularly rich in New York State. Abundant forestland and plenty of waterways combined

to give the Adirondack Mountains, the Tug Hill country north of Rome, N.Y. and the Southern Tier, a booming lumber

trade for more than 150 years. I’ve heard estimates of nearly 150 logging camps with 7,000 lumberjacks in the Adirondacks alone during the first decade of the 20th century.

I have long been fascinated by this history and made a point to meet those individuals who remembered

it before they were gone. I jotted down this note at an informal gathering of former timber industry workers in the 1980s, hosted by Joe Conway and archivist Mary Teal of Lyons Falls, New York: “The tall spruce strains, and then with a c-r-r-r-r-rack! falls to the forest floor with a thud. Swampers move quickly, trimming the evergreen giant with chain saws buzzing and sawdust flying.”

In the days of the New York ‘jacks, it is easy to imagine someone uttering that iconic cry of “Tim-BERRR!” when that spruce hit the ground. Tim-BERRR! has always had a twofold meaning in logging jargon. Since the days when choppers traveled by the light of a lantern into the woods, it has been a warning call from the feller of a tree to all within the sound of his voice to be careful because a forest patriarch is hurtling down. Bellowed in a woods-worker’s tavern, it also was, and is to this day, a summons to all at hand to share in the caller’s generosity to “belly up to the bar.” For both reasons, that iconic word will continue to resonate in the Adirondack and Tug Hill woods and taverns, recalling a olorful past and promising a productive future.

Another story I remember about the old New York lumber camps is the following remembrance of Norman R. “Norm” Griffin.

COURTESY LAWTON L. WILLIAMS

Unidentified Gould supervisor and Louie the road monkey at his station on the sand hill that led down to the Moose River Landing.

Norm was seventy years old and living in Homer, Alaska, when I last interviewed him in 1986. He worked for The Gould

Paper Company in 1936. The passage of time had not dimmed his memory. Norm assured me, “Those are the kind of reminiscences that I’ll never forget.” He said it was during some hard times in America. I was nineteen years old. My brother, Red, was eighteen. I had worked on a farm from the time I was eleven years old until I was nineteen, then I joined the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), staying until I was twenty-one. The Three Cs is one thing that shaped my life along with the brief time I was with the loggers.” He supposed it was the camaraderie of shared accomplishment and a feeling that he was a part of a big family in both the CCC and with Gould. He felt it “was unmistakable in that era.”

Norm talks about his logging days experiences:

“Mr. Hugh Dowling, the Bull of the Woods, put me on the payroll and sent me on to Camp 8 as a road monkey

for two and a half bucks a day with a dollar a day off for board. My task was to work on the roads which were not much better than trails in tiptop condition. Holes caused by heavy sleighs and tractor treads needed to be filled with snow and then sprinkled with water so the snow would freeze and form a solid and safe foundation. Soft roads, holes and bumps

could cause breakdowns or worse – disasters.

“We were roused at 5 AM for breakfast. One guy used to say how good they were to us. Wake us up in the middle

of the night to feed us. After breakfast we went out to inspect the roads under our charge and shoveled snow into the road from the sides. It was hard work but most of us were pretty tough and didn’t complain. It was dark so early in the morning, so we worked by the light of kerosene lanterns mounted on long poles stuck in the snow. Some called it ‘daylight on a stick;’ others called it ‘moonlight in the swamp.’

We chewed plug tobacco because if we stopped to light a cigarette the boss would growl at us. At that time, I was the youngest one in the camp, but everyone treated me very well. I heard many wonderful stories, true and otherwise. I also learned some verses of traditional logging songs. One song is about a fight that went on for forty minutes involving a Christian logger named Jack Driscoll, during which he lost two teeth and his opponent, Bob, who lost an ear. Here’s

a bit of it:

Jack he got Bob under

And he slugged him once or twice;

And Bob confessed almighty quick The divinity of Christ.

So fierce discussion ended

And they rose up from the ground;

Someone brought a bottle out And kindly passed it around.

And they drank to Jack’s religion In a quiet sort of way.

And the spread of infidelity

Was checked in camp that day.”

More of Norman Griffin’s logging memories appear in Adirondack Logging: Stories, Memories, Cookhouse Chronicles, Linn Tractors and Gould Paper Company History from Adirondack and Tug Hill Lumber Camps (In the Adirondacks, 2019

COURTESY DOROTHY PAYTON

A Linn tractor with log-loaded sleigh headed to the Moose River Landing.

Tug Hill Storytelling: I was fortunate to know Matthew Joseph “Joe” Conway. Joe, a native of the Tug Hill region of New York

A Look Back In Time

An article printed in “The Northern Logger “, Sept.. 2021

In the fall of 1977, I sat among former lumbermen at Joe and Madge Conway’s home in Woodgate, New York. I was there to attend story-telling sessions about the old days held at the Conway home. I was fortunate to know Matthew Joseph “Joe” Conway. Joe, a native of the Tug Hill region of New York, was born in Highmarket and grew up in Port Leyden, a logging community, surrounded by old- timers and characters who ran the gamut of trades. Loggers and lumberjacks – actually anything related to the old days of the logging industry – were his favorite hobby because he related to the forest and the people who used to call it home.

At the Conway house, I heard a lot of bragging about the old days, but these stories were also a proud reflection of the men’s local history. There may have been a bit of grandstanding …did anyone really believe the story about a logger darting from a bank, jumped into a river with a loud splash, and began racing across the surface on nimble feet, with only his speed and a fringe of scales on the sides of his webbed toes keeping him from sinking?

Maybe not, but it didn’t matter. Joe’s confab sessions with old-time loggers were a sensation. He was witty and always colorful. I was invited to attend evening gatherings with Lyons Falls, N.Y. Gould Paper Company factory employees, former ’jacks, river drivers, road monkeys, men who were part of loading crews, Linn tractor drivers, and other hard-working, brave and trustworthy men-of-the-woods who had been involved in the operation of lumber camps and various logging operations. The diverse crowd was much like the multi-hued outburst of fall color outside Joe’s living room. Autumn was the time we typically gathered. Unfortunately, as I think back, I wish I’d had the foresight to bring a tape recorder. I could have captured and preserved a way of life that has now vanished from the scene. At least I took notes.

Joe told me he hoped the informal chit- chat would “provide me a with a review of life in the Adirondack woods before that which is hailed today as ‘progress’ had had its effects. And, perhaps, it would provide a chuckle or two and much nostalgia.” He always concerned himself with those personal stories: During Joe’s retirement years, he turned his hand to writing regional history. He has passed on, but I have my memories and his two books Highmarket As You Were: Two Hundred Years of Tug Hill (self-published, 1977) and Port Leyden, The Iron City: A Passing Glance (self-published, 1989). Wanting to preserve as much as possible about life in the once-flourishing community of Tug Hill, he collected historical facts, maps, newspaper files, church records, and census reports, gathered family stories and pictures, and interviewed long-time natives. His personal approach to telling a story is just the opposite of how formal county histories read. He opened Highmarket As You Were by quoting Tom O’Brien’s one-page book titled Short History of Highmarket. O’Brien was an old-time Tug Hill native who Conway said wrote “brusquely, simply, and factually.”

A log-loaded Glenfield-Western “Gee-wiz” train approaches John Alger, Henry Gremo, and Henry Sattler waiting at a Tug Hill whistle stop.

COURTESY JOANNE SATTLER

This is Tom O’Brien’s entire book:

First the Indians settled there;

And the Yankees drove them out.

Next, the Welsh, Irish, and Dutch

drove the Yankees out.

Then the Polacks drove the Welsh,

Irish, and Dutch out.

Now the woodchucks are drivin’ the

Polacks out.

Conway commented that wit of the Irishman “accurately establishes the migratory order of the various nationalities who ‘Came, Saw,’ only to be eventually ‘conquered’ by the elements and changing times. Possibly the woodchucks were there all the time.”

Following the Iroquois, who as their Native American legend tells “sprang from the ground” somewhere in the vicinity of Barnes Corners, white pioneer settlers arrived. Conway states that 1814 marked the year pioneering folks made “a long arduous trip by ox cart from Connecticut up into this desolate Lesser Wilderness” (the term distinguishes Tug Hill from the Adirondacks, the “Greater Wilderness” ). The pioneers stayed, erected rough log cabins, and began clearing plots of the forest around their shelters for crops. This was the beginning of Thompson Corners, soon-to-be renamed Highmarket, Joe Conway’s ancestral home.

Today, Highmarket exists only as a name on a map. Around 1849 the Irish began to move in after they had built the Black River Canal, and soon after the Welsh, Germans, and Swiss followed. It was this pioneer era that gave way to progress. Conway wrote: “At the tender age of eleven or twelve, many [boys began to] learn the lumberjack trade first-hand” and opportunities for most girls were just as unfortunate. Some worked at home, became housemaids in surrounding towns, “or went to Utica to work in the textile mills.” Conway knew of one girl who began cooking in a lumber camp at the age of twelve, “progressing at sixteen to the same occupation on a state barge which traveled between Lyons Falls and Carthage.”

The abundance of timber brought a level of material prosperity to early Tug Hill residents.

Conway writes: “It has been recorded that between 1840 and 1860, Lewis County furnished about two-thirds of all birdseye maple used in the world, with most of this coming from the Tug Hill Plateau. The tall spruce of the plateau were in great demand for spars for the sailing vessels of the day as were the sawed softwoods for city wharves, piers and buildings. New York City and Buffalo used tremendous amounts of Tug Hill timber for their wharves and docks.

Both timber and spars were being shipped out of Highmarket as early as 1856, drawn by teams to Port Leyden and Boonville, where the spars were bound into rafts and towed down the Black River to the Erie [Canal] and beyond. Both the canal boats and the Black River Railroad transported the sawed lumber…”

Think of all the oyster kegs, barrels, cheese tubs, butter firkins, wagon tongues, flooring, pianos, spars, piles, wharves, piers, newsprint, paper bags, toilet tissue, boxes, cartons, writing paper, charcoal, alcohol, and buildings that Tug Hill timber provided. And the little town of Highmarket was a big contributor ….

Joe Conway’s brief discussion of logging reflects the industrialism and shows the true pioneer spirit that was necessary for those early lumbermen and women to settle and eke a living in the upland country known for 400-inch snow sea- sons. As one descendant remarked to Joe about those who endured the lofty plateau, “They all should have flags on their graves — just for fightin’ the Tug Hill snowstorms.”

Unfortunately, by the time Joe began gathering materials and published Highmarket, As You Were, it was too late for many personal stories. Those who could have related happenings on The Hill were gone.

Conway told of whitewater crews as “men of steel. Driving logs was no child’s game.” A force of water and logs. These grim battles relied on the ingeniousness and courage.

JIM FYNMORE COURTESY LYONS FALLS HISTORY ASSOCIATION

Last Meal of the Season: To avoid spring cleaning, there were a number of things to look after when closing camp at the end of each season.

Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes

An excerpt from ” Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes “, Starting on page 247.

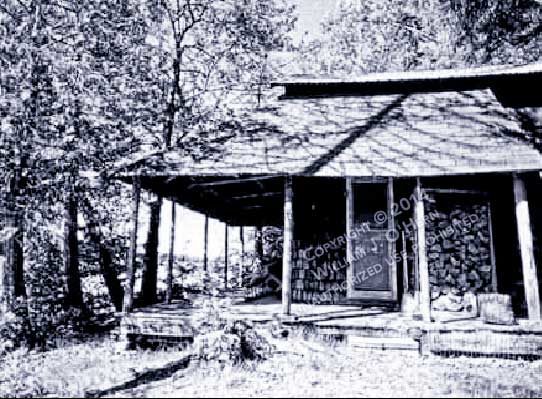

Bette and Jay’s last camp day at North Lake. “Closing camp.” The very words bring to mind a place, an atmosphere, an image of a familiar building, a covered porch where rocking and gazing, reading and telling stories took place—and the lump in the throat at having to leave it.

Photo by Wayne and Linda Cripe. Author’s Collection

TO AVOID a real spring cleaning, there were a number of things to look after when closing camp at the end of each season. Hedgehogs, chipmunks, in- sects, bees, raccoons, and mice were all waiting for the inexperienced or careless owner to vacate so they could move in, knock down, break, tear open, spill, trample on, and gnaw at. Chewing was what they seemed to enjoy most.

Camp owners have learned first-hand the cause-and-effect relationship of simply closing the camp door and leaving: unshuttered windows mean broken panes; unsupported beams crack or sag by spring. Sealed, vacuum-packed tin cans burst when they freeze; blankets, cloths and clothing left out are full of ragged holes by spring. Unprotected mattresses are a perfect nesting site for mice. Open crockery can be found filled with seeds, nuts and shucks; leaving a chimney uncapped is like posting a sign saying “Enter” or “Nest Here.” And the calling cards of rodents—the droppings— are found scattered helter-skelter.

To combat all this, there is a standard “To Do” list when one closes for the winter:

During Rev. Byron-Curtiss’ last ten years a following this list to the letter, and as a rundown.His last log entry departed from his usual ones, which often began, “Last night in Camp – duly and properly celebrated,” and which always ended by thanking God. Instead, the eighty plus-year-old man scrawled in very shaky pen strokes, “Visited camp on this pleasant day. I desired to see it one more time before snow closes in.”

“He was quiet when we turned to leave that day,” Tom Kilbourn, his driver, reported, “and that was unusual for him.” The owner never returned.

Kilbourn purchased the camp in 1953. For the next forty years he rented the lakeside building on a yearly time-share basis.

On Bette’s and my final day at Nat Foster, Tom had given me all of The Reverend’s log books, personal papers, and photo albums. My plan was to write about “the Bishop of North Lake.”

I believed a recorded knowledge of the region needed to be done and I soon wrote two books: Adirondack Stories and Adirondack Influence: The Life of A. L. Byron-Curtiss 1871–1959.

Elated teenagers pose on the summit of Ice Cave Mountain after finding the famous Ice Cave. Circa 1930s.

Courtesy Thomas and Doris Kilbourn .The A. L. Byron-Curtiss Collection

Recipes from Yesteryear:

Lone Pine Backed Mac & Cheese with Broccoli: Directions: Cook macaroni, adding broccoli during the last four minutes of cooking time. Drain.

Recipes from Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes

An excerpt from ” Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes “, Starting on page 247.

Ingredients:

2 cups uncooked elbow macaroni.

1 cup broccoli florets (fresh or frozen). 5 tablespoons butter.

2 tablespoons flour.

2 cups milk.

½ teaspoon salt.

8 ounces cheddar cheese cut into ½-inch pieces.

½ cup dry bread crumbs.

Directions:

Cook macaroni, adding broccoli during the last four minutes of cooking time. Drain. Melt 4 tablespoons butter, stir in flour. Cook over heat, stirring for about 1 minute until it bubbles and looks smooth. Add milk and salt. Cook until sauce thickens. Add cooked macaroni, broccoli and cheese. Stir until the cheese melts. Spoon into an ungreased 2-quart casserole. Melt remaining butter. Mix bread crumbs over the macaroni and cheese. Bake 20-25 minutes at 350°F. until golden brown.

Recipes from Yesteryear:

Orange beef sandwich: In 8-inch square glass baking dish, arrange meat slices in single layer and sprinkle with a little rosemary and salt.

Recipes from Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes

An excerpt from ” Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes “, Starting on page 223.

Ingredients:

¾ pound roast beef, sliced thin.

½ teaspoon rosemary, crumbled. Salt to taste.

1 cup orange juice.

3 crusty sandwich rolls, split and toasted if desired. Ginger Mayonnaise.

Lettuce leaves.

Directions:

In 8-inch square glass baking dish, arrange meat slices in single layer and sprinkle with a little rosemary and salt. Repeat layers, then pour orange juice over meat, cover and refrigerate 1 to 2 hours. Drain well. Spread rolls with Ginger Mayonnaise. Arrange meat on roll bottoms and top with lettuce and roll tops.

GINGER MAYONNAISE

Combine ¼ cup mayonnaise and ½ teaspoon ground ginger

IT HAS BEEN a long time since I first summited Ice Cave Mountain for a look at the so-called ice cave on the peak.

Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes

An excerpt from ” Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes “, Starting on page 223.

On the heels of numerous newspaper reports about women exploring for the deposit of perpetual ice “caused by convulsion of nature,” written by Rev. Byron- Curtiss, the stories attracted the attention of adventurous people. The Reverend offered all who would bring a sample of the ice to his camp a notarized statement of success and a picnic at his lodge. Courtesy Thomas and Doris Kilbourn

The A. L. Byron-Curtiss Collection

IT HAS BEEN a long time since I first summited Ice Cave Mountain for a look at the so-called “ice cave” on the peak and a picnic overlooking the balancing rock. I’ve taken many hikes to it since then. It’s a favorite late spring or fall trip, but not a destination recommended during the buggy portion of the year.

A reporter, Linda Murphy, and photographer, Heather Ainsworth, from the Utica Observer-Dispatch accompanied me on a trip to the summit one autumn day. Their actions provided me some silent laughter. I had cautioned the women to dress appropriately and to be prepared to trek over a blind path — my term for an unmarked but visible (to a degree) pathway. They seemed in high spirits and alert to hazards until they realized a fact I had not paid any attention to. Almost in unison they exclaimed, “We’re in the wilderness!” When I asked what they meant, they pointed to their cell phones. They were not getting any reception. I suggested something along the lines of trying to concentrate on the beauty of the surroundings rather than the stark terror of an afternoon without a smart phone.

I remember that hike because of the sandwich I had experimented with as I packed my lunch that morning, because the women were good sports even when the walking turned rough. Irregularities became hidden traps, branches slapped them when they walked too close to each other, and briers clawed at their clothing. As I enjoyed a leisurely rest and late lunch, they commented that they were going to see where their cell phone reception would pick on their way out of the woods.

The reporters seemed uninterested in the gourmet sandwiches I’d brought for them, not really tasting them as they held their phones up in various directions, still perplexed and dismayed by their disconnection with civilization.

As we passed the North Lake sluiceway I pointed out the boarded-up State House and told a story about Anna Brown, a locally known cook. Patrons raved about her table fare and often left with a favorite recipe to try in their own kitchens. Summer residents and campers all raved about her Sunday standard of eggs, bacon, and biscuits with chicken gravy, a breakfast she used to serve in the large dining room.

I wondered what Anna might have thought about my cold sandwich. Knowing her wizardry, I think she would have given it a thumbs up. I know I did. I wrote it down, too —with a pen, on a recipe card.

Elated teenagers pose on the summit of Ice Cave Mountain after finding the famous Ice Cave. Circa 1930s.

Courtesy Thomas and Doris Kilbourn .The A. L. Byron-Curtiss Collection

Roy Wires fished for trout on the lower end of the West Canada Creek. Roy almost lost a big trout when it snagged on junk.

Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes

An excerpt from ” Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes “, Starting on page 213.

Emily Mitchell Wires preparing her Tomato Wiggle.

Courtesy Roy E. Wires (The Emily Mitchell Wires Collection)

AS A TEENAGER living in Herkimer, NY, Roy Wires fished mostly the lower end of West Canada Creek, limited by how far he could ride his bicycle. Middleville, about 8 miles up Route 28, was pretty much his limit. This stretch of the creek flowed mainly through farmland, and unfortunately, many times the creek banks became a farmer’s personal junkyard. It was not unusual to see old car bodies, worn-out farm implements, barbwire, and other junk discarded over the bank. The only problem was, in times of spring thaw and the resultant high water, many of those items got washed into the creek.

Roy inherited his love of fishing from his father Edwin and grandmother Emily.

Courtesy Roy E. Wires (The Emily Mitchell Wires Collection)

It was one of those items that one day almost cost Roy a big trout. Back in the days of this story, the dam on the West Canada Creek at Trenton re- leased water almost every afternoon to generate electric power. This of course resulted in the creek downstream of the dam rising 12 to 18 inches every afternoon and evening.

It was one of those late afternoons that Roy was spin-fishing a stretch of the creek with his favorite lure, a gold phoebe. After what had been a less than fruitful day up to this point, he hooked a nice brown trout that did a couple of cartwheels and then started digging deep. It was obvious that this brown trout knew his way around the creek; all of a sudden the line became tight. Although the fish was still hooked, as he could feel him and see an occasional flash out in the stream, Roy just couldn’t get him in. The only alternative was to wade out to where he was, and see what he was hooked on.

The fish had swum through a big roll of discarded barbwire. Roy knew there was no way he could thread him out of that mess, and wondering how long his four-pound test line was going to hold up, he started letting out line, hoping it would pull him downstream and he could net him below the coil of barbwire and then once he had him in the net, he would cut his line, and pull it through. Well, this sounded like a good plan, until the water started rising from the afternoon discharge at Trenton. Roy had already just about reached the limit on his hip boots getting to the fish, and knew that the rising water would flood his boots and he was going to be in real trouble.

“Standing on my tiptoes with the water coming up rapidly,” he remembered, “I was finally able to net my fish, a nice 15-inch West Canada Creek brown trout. At that point I just cut my line and headed for the bank with the trout. ‘Farmer Brown’s’ barbwire had almost cheated me out of a real prize trout, and the Trenton discharge of water was close to closing the deal on netting that trophy. I guess the fishing gods were with me that day.”