I immediately liked Nitty. He and his buddies back at camp play a part in the true story of the history of the backwoods of Atwell, New York.

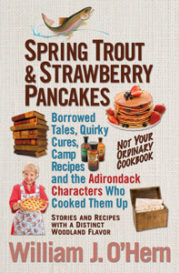

Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes

Back at Camp

An excerpt from ” Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes “, Starting on page 2.

“An uneventful day at camp save a brief call by “Joe” Jenkins, the state game warden, accompanied by a young man named Yerdon and another warden. They were looking for Fred Owen and a Roberts of the Red Camp party for killing a doe. I am sorry if Mr. Owen is in trouble, for he is a good man.”

— Rev. A. L. Byron-Curtiss, Nat Foster Lodge Log Book, Nov. 14, 1933.

“Camp Mayhew became the ‘Red Camp’ on August 20, 1972, the date the faded white clapboard siding was painted red.” —Harold McNitt. Adirondack porches are places to relax and enjoy a cool breeze on a warm night—a place for eating, reading, rocking, and storytelling.

Courtesy Meredith Flerlage

THE RED CAMP was a cheery-looking place that for many years had known the gentle touch of George Hoxie’s attentive handyman skills. Once, it was a rambling, squatty, out-of-square building with hand-split cedar shingles fashioned by native Owen “Kettle” Jones. Jones came by his nickname from making a wild berry brandy-of-sorts in his mountain still. Hoxie enjoyed telling tales about hermit Kettle and his pet raccoon’s fondness for the homemade brew, which they shared in the backwoods beyond Hoxie’s place. George and all who used the camp loved the Adirondacks.

A dirt dogtrot connected Red Camp to Drs. Jones-Fuller Camp and the Wiggins Camp, and on to Nat Foster Lodge, along North Lake’s shoreline. The Red Camp’s porch roof shaded and sheltered those who rocked on the plank porch below, perhaps wrapped in a light robe against the morning chill, as they watched the warming morning rays of the sun burn off wisps of fog that draped over the lake’s surface. During the day, campers gathered to do nothing other than to relax, nibble camp-standard cookies and enjoy being at a much-beloved location—the lakeside.

Harold McNitt was the senior partner of Red Camp. As a boy, McNitt was called a “whippersnapper” in what he believes was the best sense of the word. Rev. Byron-Curtiss, a close adult friend who lived at Nat Foster Lodge, assured him it was a term of endearment. McNitt had been coming to North Lake since 1922. He said he had never missed a year.

“Call me Nitty,” he instructed me as he introduced himself. We were sit- ting in the shade on the porch, and it was the summer of 1996. As we shared bits about our background I learned the camp had been his wood- land home since he was a young child. “I’ve baked some cookies. Come into the cabin kitchen,” he motioned. We continued our chat by an old- looking wood cook stove, surrounded by spic-and-span wood-paneled walls that had been painted white.

Sitting at a century-old kitchen table, Harold closed his eyes and recited this simple poem he had written.

North Lake, My Treasure

“The ducks will always visit North Lake camps for bread. Every day the loons will sing their magical phrases

And sometimes do their dances by Blueberry Island.

For every year the magic of North Lake,

The most beautiful place on earth,

Sends out its magnets to draw its real lovers back.”

I immediately liked Nitty. He and his camp buddies play a part in the true story of the history of the backwoods of Atwell, New York.

I had come to learn about Nitty’s family connection with the so-called “Bishop of North Lake,” the Reverend Arthur Leslie Byron-Curtiss. I was researching the Episcopalian minister’s life for a biography.

“The Reverend stayed over there (Harold pointed with his finger.) for months. He was often the sole inhabitant on this side of the lake. There were only a few camps over there in the cove. Byron-Curtiss walked a lot. He enjoyed it. I remember him always clean and neatly dressed. His clothing never smelled smoky. He wore serviceable North Woods attire. He was an affable person, a man you liked being around as a kid. I went over to his camp often. He told lots of stories; we often talked fishing.

“Once I earned ten dollars. There was a party of men drinking over there. They had cases of beer. Whiskey bottles were everywhere. So, too, were many cans of pipe tobacco and Sweet Cuba chewing plugs. They weren’t in much of a climate to clean the bullheads they had caught. One fella asked me if I’d do it for them. I didn’t mind helping. Besides, I knew The Reverend would include me in the group’s fish fry. I got me a log, took a nail, drove it with a hammer right through the fishes’ heads, cut the back fin right off and skinned them outright. Well! Much to my great surprise ‘B-C,’ as he liked to be called, proposed they pick up a collection for me. One dollar was a lot of money back in those days, so you can imagine the value of ten dollars — a small fortune!

“The McNitts were singers, good ones. Sometimes we sang on the porch. I often joined in. If you were out on the water you could have heard us at Mayhew Cove. ‘Course everything is so quiet up here, voices carry across the water clearly.”

Nitty was neither a guide nor native woodsman, but I found him to be a natural outdoorsman and someone who thoroughly enjoyed camp life. His cheerful humor, his resourcefulness, his knack for remembering yarns, and his complete accord with the serenity of nature helped me understand how thoroughly imbued he was with the woods and waters and how the Adirondacks had influenced his growth throughout the years.

Nitty also baked rich, tasty fundamental cookies, a weakness of mine I fight because they are loaded with saturated fat and cholesterol—a fact Nitty quipped made them “honest to goodness baking. That’s why they taste so good.” Nitty’s recipe is simple:

Nitty said his grandmother had taught him to make cookies, pies and biscuits as well as other things. Nitty had thought about having a little camp garden, but would have had to fight off the critters. He liked to hang his laundry to dry on lines stretched between trees in the fresh mountain air. We stood side-by-side at the white-enameled sink and looked at old snapshots tacked on the wall. He pointed out a picture of himself as a young kid. Once, when he was cutting shapes in sugar cookie dough his grand- mother had rolled out, she told him a baking secret: rum doesn’t count as alcohol if it’s drenching your fruit cake.

Nitty enjoyed living off the grid in a turn-of-the-20th-century Adirondack cottage complete with a canoe, a rowboat and a boat with a small outboard engine. He drew water from a spring, bucket by bucket, and used a buck- saw and sawhorse to work up wood for fuel. It was an idyllic mountain-spun life. Inspired by those pioneer years, his ancestors, and the elderly Atwell natives, he’d spent a lifetime learning about old-timey ways, backwoods cooking, common wisdom and tall tales.

Harold McNitt, far right, with his uncles, taken at the foot of North Lake.

Courtesy Harold McNitt

RED CAMP SUGAR COOKIES

2 cups sugar.

1 rounded cup of butter.

4 eggs.

4 teaspoons baking powder.

4 cups pastry flour.

Vanilla.

Roll, cut and bake.