Ma Getman recipes: Ma Getman was an excellent cook. Her services offered no frills but that was made up by her mothering her boarders.

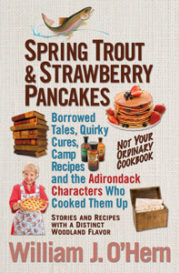

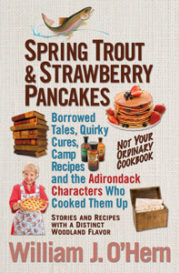

Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes

The Recipes of Ma Getman

An excerpt from ” Spring Trout and Strawberry Pancakes “, Starting on page 125.

MA GETMAN was the owner and operator of the Getman House in Forestport. Rev. Byron-Curtiss boarded there during 1892-93. “Ma Getman,” he remembered, “was a widow and she tried to make her hotel as much like a home as possible. Ma was a square-shooter and an excellent cook. Her services offered no frills but that was made up by her mothering her board- ers. We loved her and never let her down.

“Right from the start, Ma gave me a sound talking to. ‘Now look here son,’ she said, ‘you have been on ice long enough …you’re young. You should kick up your heels and prance a bit; the good Lord meant that you should have a little fun now and then, but don’t you go rambling around in them woods without you having somebody with you that knows his way around. We like your preaching and we don’t want to have you turn up missing at the Sunday services.’”

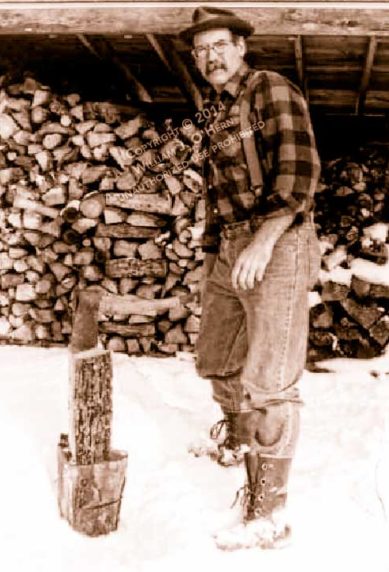

Charlie O’Conner rented the bar concession at the Getman House. Bryon- Curtiss and O’Conner became good friends. The Reverend said he “initially shied away from the saloon portion of the hotel.” In those days, he pointed out, “the local community didn’t want their preacher in such places.”

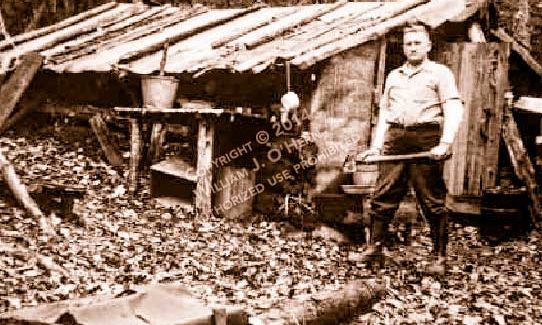

Byron-Curtiss tells of Ma Getman’s thoughtfulness the day he investigated an old cabin for sale. “I was forewarned the building was not much to look at, yet it was placed on a fine piece of land, a wooded site snuggled among the trees. Price: $15 with a quitclaim deed.”

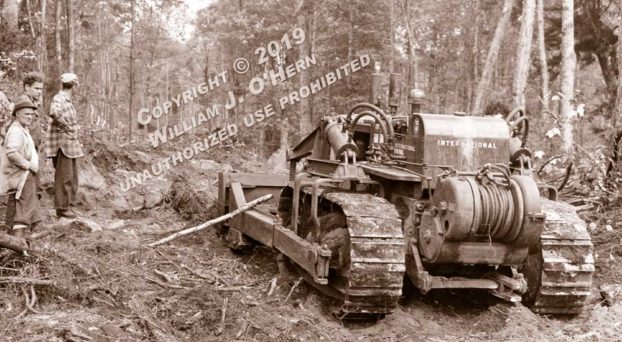

Charley O’Conner claimed a man could put on some weight eating Ma Getman’s cooking.

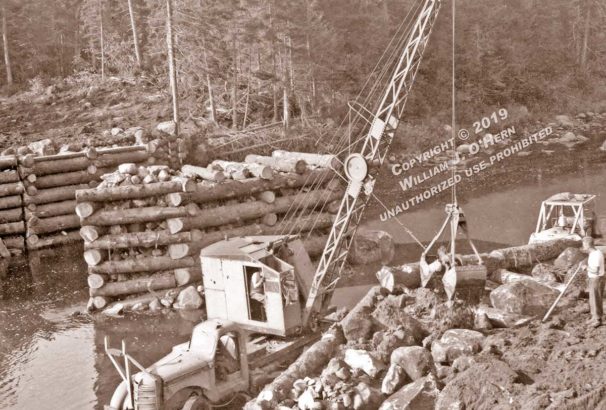

Courtesy Dorothy Mooney

“Ma and W. R. Stamburg, my senior warden and as such my right-hand man at Christ Church, said I needed a break from work. All knew of my interest in the lake country. Stamburg and O’Conner volunteered to ac- company me to see the North Lake property. After an early breakfast at Getman’s, we men, in a heady, cheerful mood, were off with a food basket provided by Ma. She packed ham, sausage, bacon, and salt pork—meats that would stand the long (and non-refrigerated) sixteen-mile trek, and spice up the men’s palates and offer a food donation to the table of Cool’s Mountain House, where we planned to board that night.” In addition to the prepared meats, they also carried “a loaf of bread, fresh eggs packed in corn meal and several dozen crispy fried donuts.”

The men stopped at Mulchy Spring for lunch, where they ate Ma’s fruit bread. Her recipe evidently sparked The Reverend’s interest, because it was found in his camp cookbook.

Byron-Curtiss said of Ma, “She gave generously of her modest means to the church and she had the Ladies’ Aid meet frequently in the parlor of the hotel, where she served a generous luncheon.” The Reverend was al- ways the recipient of any leftovers.

In addition to Ma’s generosity and home-cooking, Byron-Curtiss acknowl- edged his second love was Ma’s beautiful daughter. “I fell head-over-heels under her influence. I was so serious that I talked over the prospects of marriage with Ma. She took the more sensible attitude, assuring me that my romantic feeling would pass. She knew I intended to leave Forestport to pursue advance work. She was right, but we remained friends the rest of our lives.”

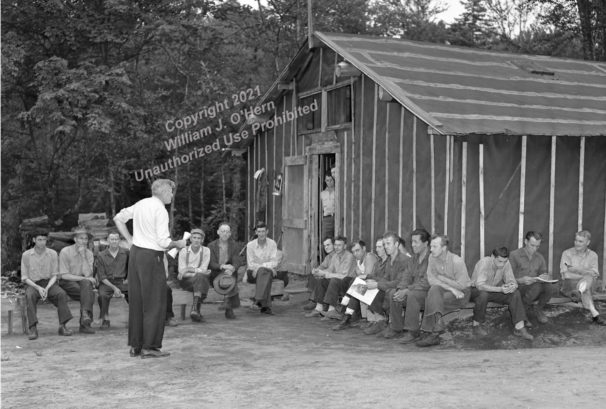

The Getman Hotel, Forestport, N.Y.

Courtesy Leola Schmelzle