Visualize how America’s Great Northern Forest would have appeared if seen from above in 1820, stretching from Minnesota to Maine. Imagine a sea of continuous forests comprised of a mix of softwood and hardwood trees: Miles

upon miles of spruce, balsam, pine, birch, maple, beech, cherry, oak, chestnut, and other tree species spread across a great expanse.

Twenty years later, pioneer families that immigrated to America pushed westward from New England, where small towns had grown to metropolises. “Long lines of people had been coming into the country as the result in part of the 1848 revolutions in Europe,” explains Tug Hill author Thomas C. O’Donnell. “Europe was demanding more and more American grain, the Central States were producing untold quantities of it, and labor was being imported from Europe

to build railroads and ships to carry the produce.” Once wilderness, the character of the land was changing from farmland to booming cities. O’Donnell continues, “Homes had to be built to house the new populations, and harbors and docks for accommodating the ships. America was fast becoming industrialized and one of the industries

that matured over night was lumber.” With so many office buildings, factories, wagon-and barrel-making shops, docks,

shipyards, and so many other businesses being built, wood was in high demand.

By 1850, logging companies were actively harvesting America’s forests from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic seaboard.

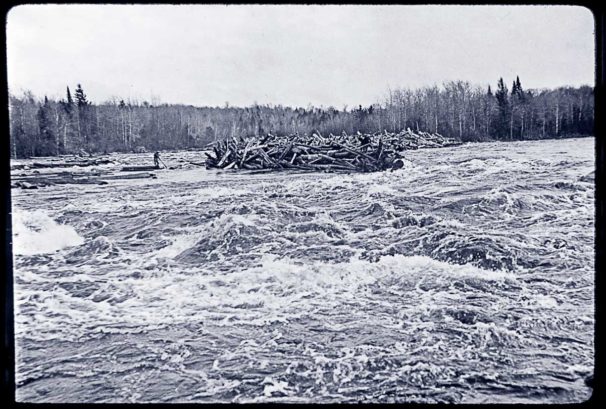

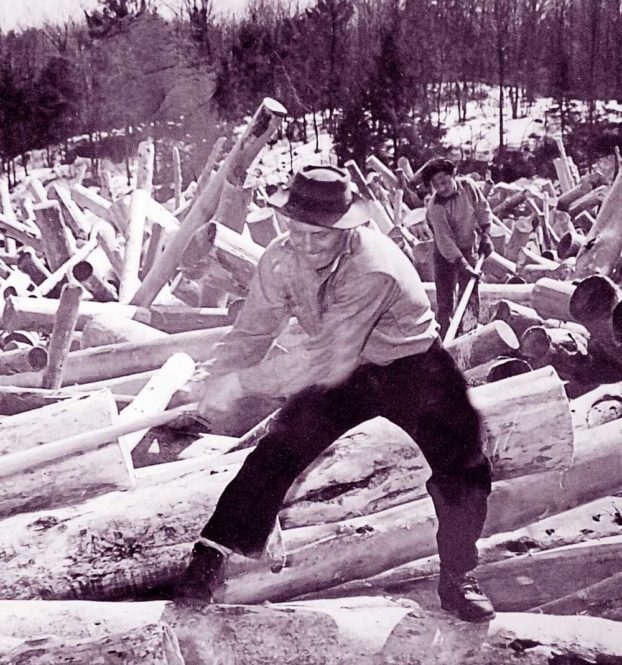

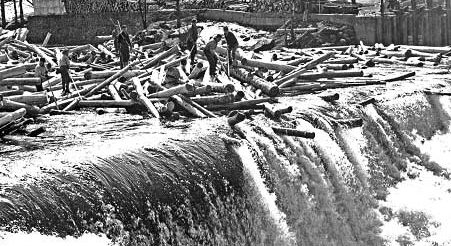

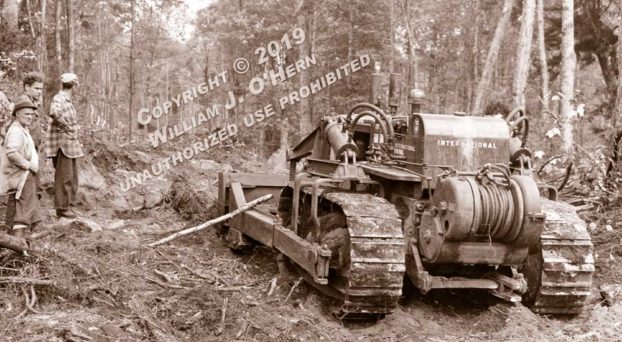

Equipped with double bitted axes and crosscut saws, lumberjacks felled trees and skidded logs with horses

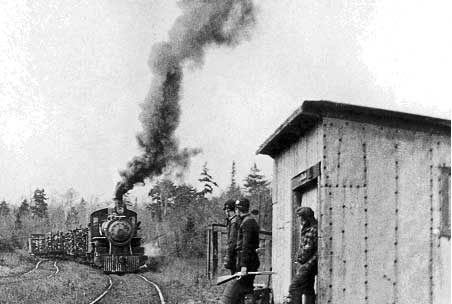

to rivers and floating the logs to mills. Twenty years later, logging companies that cut hardwood trees – trees too heavy to float on rivers – loaded them onto flat cars and transported them to sawmills by train.

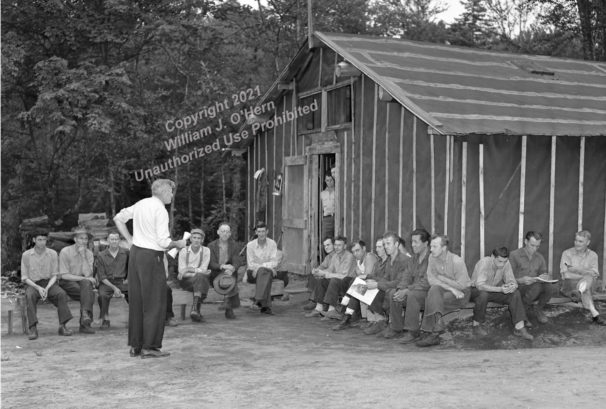

As logging diminished the virgin forests, concern for protecting and preserving vital forests for future generations emerged among the public. Scientific studies, often from Europe, in the new field of silviculture advanced woodland knowledge. Foresters, trained professionals who studied what we today call forest sustainability, appeared on the

scene. Loggers became educated and imparted their knowledge to other loggers. No one wanted to see forest

land disappear, nor did they want a way of life to come to an end.

I enjoy listening to older loggers talk about their careers in the woods. Some of their tales about their experiences can create a lot of nostalgia. Learning about the evolution from old-style logging to mechanized methods is a reminder of the advancements in technology seemingly realized in a short period of time. There have been stories that made me laugh and others that amazed me, but the true stories of averting danger and death are reminders of how dangerous the job could be in the old days of logging and even today.

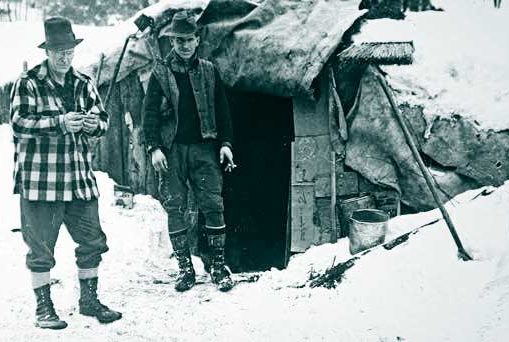

The Adirondack logging careers of those I’ve spoken with and heard about have been an eclectic mix: forester, cook and cookie (a cook’s assistant), teamster, mechanic, Linn tractor driver, camp clerk, blacksmith, truck driver, chopper, notcher, spudder, road monkey, swamper, straw boss, river driver, dynamite expert, cat skinner, whistle punk.…A complete list would be as long as a pike pole. Most often, the drama of an Adirondack log drive relived decades after still dwells within the heart of a lumberman, and for the outsider is a reminder that log driving was serious business. Today’s loggers and sawmill workers are contemporary business owners and workers in a global industry. The industry includes workers who do everything from haul logs from the forest to produce paper, furniture, baseball bats, and countless other wooden items.

Logging has moved into the 21st century, but the memory of an earlier time remains – the time of lumberjacks and lumber camps. While the colorful old-style ’jacks, fiercely proud teamsters, inventive blacksmiths, prima-donna cooks, log-hopping whitewater men and river hogs have passed on, logging goes forward. Meanwhile, their history continues to draw attention to their times.

The history is particularly rich in New York State. Abundant forestland and plenty of waterways combined

to give the Adirondack Mountains, the Tug Hill country north of Rome, N.Y. and the Southern Tier, a booming lumber

trade for more than 150 years. I’ve heard estimates of nearly 150 logging camps with 7,000 lumberjacks in the Adirondacks alone during the first decade of the 20th century.

I have long been fascinated by this history and made a point to meet those individuals who remembered

it before they were gone. I jotted down this note at an informal gathering of former timber industry workers in the 1980s, hosted by Joe Conway and archivist Mary Teal of Lyons Falls, New York: “The tall spruce strains, and then with a c-r-r-r-r-rack! falls to the forest floor with a thud. Swampers move quickly, trimming the evergreen giant with chain saws buzzing and sawdust flying.”

In the days of the New York ‘jacks, it is easy to imagine someone uttering that iconic cry of “Tim-BERRR!” when that spruce hit the ground. Tim-BERRR! has always had a twofold meaning in logging jargon. Since the days when choppers traveled by the light of a lantern into the woods, it has been a warning call from the feller of a tree to all within the sound of his voice to be careful because a forest patriarch is hurtling down. Bellowed in a woods-worker’s tavern, it also was, and is to this day, a summons to all at hand to share in the caller’s generosity to “belly up to the bar.” For both reasons, that iconic word will continue to resonate in the Adirondack and Tug Hill woods and taverns, recalling a olorful past and promising a productive future.

Another story I remember about the old New York lumber camps is the following remembrance of Norman R. “Norm” Griffin.