Once, sportsmen and tourist propaganda depicted exciting experiences. Sportsmen sojourned in hunters’ camps – bark or pole lean-tos provided by guides. Continue Reading Adirondack Characters and Campfire Yarns – Sportsmen’s Camps and Backwoods Destinations

Adirondack Characters And Campfire Yarns

Sportsmen’s Camps and Backwoods Destinations

An excerpt from ” Adirondack Characters And Campfire Yarns “, Starting on page 177.

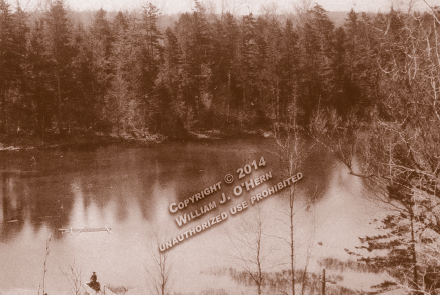

AS NEWSPAPER COLUMNIST, author of West Canada Creek, hiker and kayaker David Beetle so often put it, “The West Canada is a good river to know.” Beetle would know. Over the course of a year he tramped his way up and down the stream, interviewed hundreds of old timers, and braved the upper West Canada Creek’s powerful rapids many times in his wooden kayak, all in the name of research to gather the first written history of the river’s 75-mile course.

Mud Lake is the source of the watercourse. The river winds southwest toward Prospect, fed by outlets from a maze of Adirondack lakes. The mountainous country was once home to Louis “French Louie” Seymour, who lived on the shore of Big West. The West Canada Lakes are distant and hard to reach, but the remoteness doesn’t bother the backpackers who, if they arrive during just the right stretch in June, will find the shorelines abloom with pink azalea. Nature’s palette has daubed the West Canada Creek wildwood trails in year-round witchery, from the budding softwoods and hardwoods of spring to the snow-clad evergreens of winter. The entire region was once under the last glacial ice sheets that blanketed the Adirondacks. The glaciers were responsible for shaping the current landscape. Their receding waters left a vast number of boulders and erratics everywhere.

“This wild, hour-glass-shaped high plateau is higher than any other Adirondack land mass.” At an elevation of 2,458 feet, Wilmurt “is the highest settled lake in the Adirondacks.” Fort Noble Mountain, the highest surface feature in the region, is in the Town of Wilmurt. A fire tower was once constructed on the summit; observers looked out over Nobleboro, West Canada Creek and the South Branch of the West Canada Creek in Herkimer County. Its slopes are a sweep of scented winds over balsam, spruce and pine, and are costumed in brilliant fall colors for leaf peepers, ranging in hue from red to pale yellow. Author Barbara McMartin’s Discover the West Central Adirondacks guidebook tells us about the southwest Canada Lakes Wilderness: “Although many trails penetrate its narrow core, parts of it are trackless, making it the most remote and secret area in the park … The creeks conceal spectacular forests as well as a dozen inviting lakes.” The guidebook reports that “There is currently no view from … (Fort Noble Mountain]. In its last few years, when the tower stood abandoned, you could still climb its rickety stairs for the view. However, even to do this you had to ford the South Branch, no mean feat even in low water, because the great hiker’s suspension bridge was removed about 1980.” The “160,000 acres (would be] the second largest Wilderness Area (after the High Peaks in Essex Country) in the Adirondacks, a bushwhacker’s paradise were it not for the difficulty in fording the South Branch and the large blocks of Adirondack League Club and Wilmurt Tract lands that are posted.” McMartin’s guide emphasizes that the owners “permit no one on their lands.”

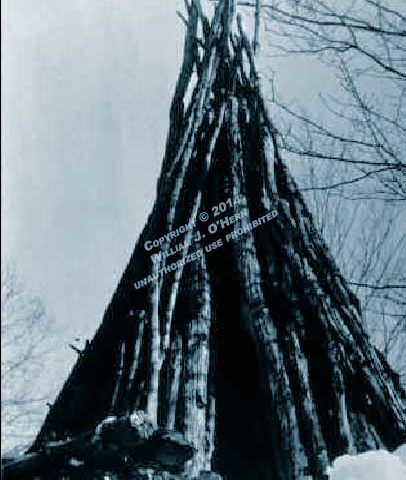

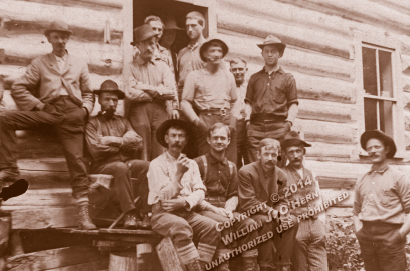

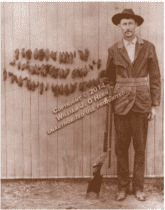

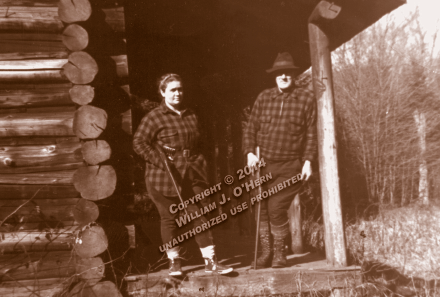

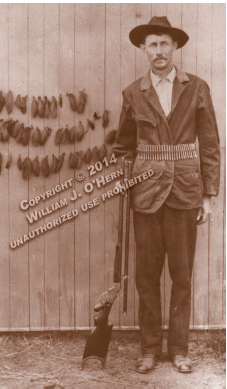

Once, sportsmen and tourist propaganda depicted exciting experiences.

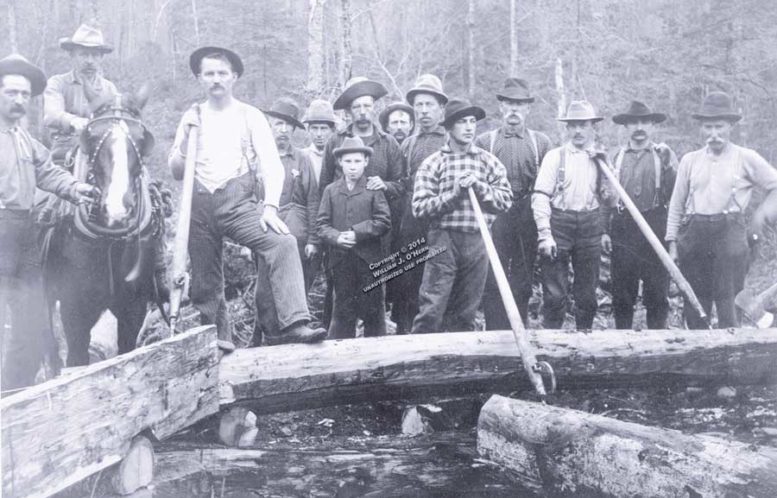

Sports sojourned in hunters’ camps – bark or pole lean-tos provided by guides who selected camping grounds, felled trees and peeled bark for the shanties, fitted up enticing balsam bough beds on the floors, built shelves and racks, kept the campfires and smudges going night and day, prepared and cooked the meals, washed dishes, told yarns and, late nights or early mornings, left the sports to sleep while they slipped away to return with venison or fish. Those recreationists who sought a woods experience but had more congenial tastes, wishing to avoid living in the heart of the woods but preferring the charms of hotel life to those of camp life, sought out public houses with unpapered pine board partitions rather than the hotels with covered verandahs, barrooms, bedrooms, bathrooms to wash off the dust of forest travel, and dining rooms that offered a well-arranged menu from which to select dinner.

The stories in this chapter touch on a few of the high spots Blankman and Norton learned of or visited in their days of circling the Adirondacks. Most deal with the forest and lake settings in the West Canada region. Almost every turn they took brought them to a point of interest-Spruce Lake, now wild, once filled with trout-Adirondack Whiskey Springs, a lake bed containing an interesting natural resource, and more.

Reading the old recollections is an excellent way to get that old-time “forest feeling.” And it’s invigorating.