An excerpt from Chapter Two of the Moose River Plains, Vol. 1

TRY DEFINING VACATION. Simply, taking a vacation is often a necessary break in life’s routine. But, when I attempted to widen the definition beyond my center of expectations, I wasn’t surprised to find there is no one easy definition. A single person’s vacation is different from a couple’s vacation, and a couple’s vacation time is different from that of couples who vacation with children. Personal preferences influence what constitutes a vacation, as do one’s financial resources.

And, what is the “ideal” spot? A vacation can be like riding a rollercoaster with lots of ups, downs, twists and turns! I learned a bit about a remarkable Adirondack vacation when I met with Farrand N. Benedict Jr. at his East Lake Road home in Skaneateles, New York. On that day he handed me a copy of a collection of handwritten letters that described an unbelievable arrangement of trips in 1873 made by a collection of ladies who planned to connect at “the lake of the skies,” their expression for Blue Mountain Lake.

In the spring of 1873, a group of idealistic and scientific-minded women who chose to assume names related to goddesses or characters from Greek and Roman mythology decided to leave civilization on an adventurous botanical expedition to study nature – particularly botany in the heart of the Adirondacks’ millions-of-acres of wild land. Guided by thirteen of the most reputable guides of the day, Themis (Miss Steele), the head of the botanists, drew up plans to split the women into four groups:

1. The Schroon River Section

2. The Saranac Party

3. The Moose River Party

4. The Lake Pleasant Section

She wrote of the teams:

Ladies are much better qualified for the varied and arduous duties of such an expedition by their power of observation, their patient and persevering industry, no less than by their delicate touch in the manipulation of instruments and the minute organs of plants and by their intuitive sense of the beautiful.

Themis Steele

I was most interested in the Lake Pleasant and Moose River parties that Amanda Benedict reported because of my experience with that area of the Adirondacks—in fact I felt a sense of connectedness with the troupe’s vacation routes, having bushwhacked through much of the same territory.

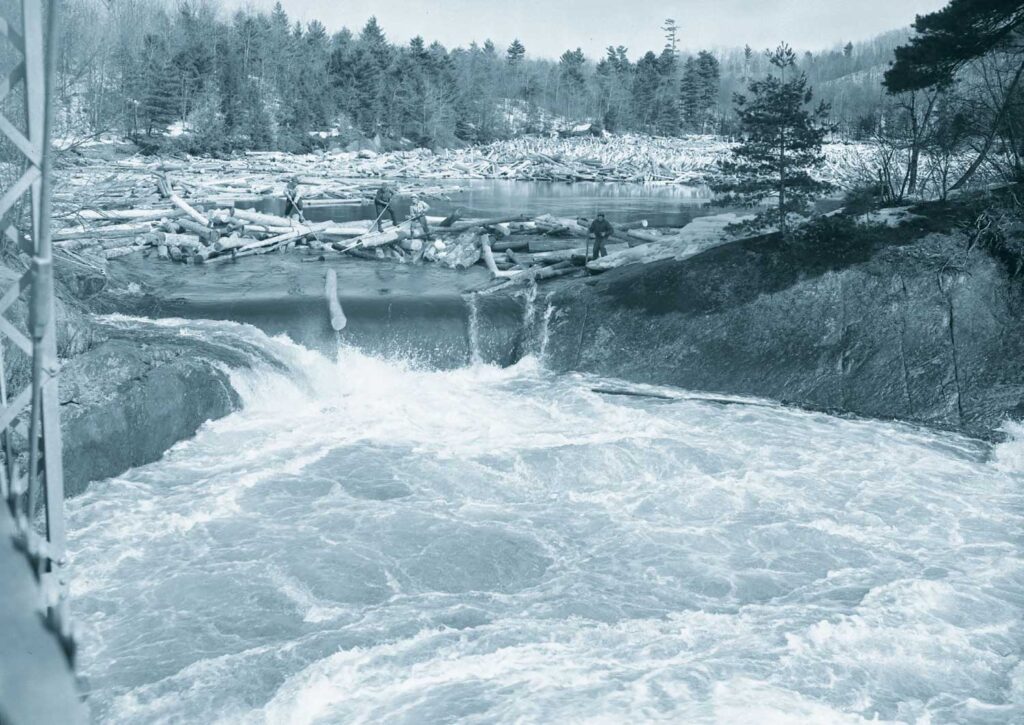

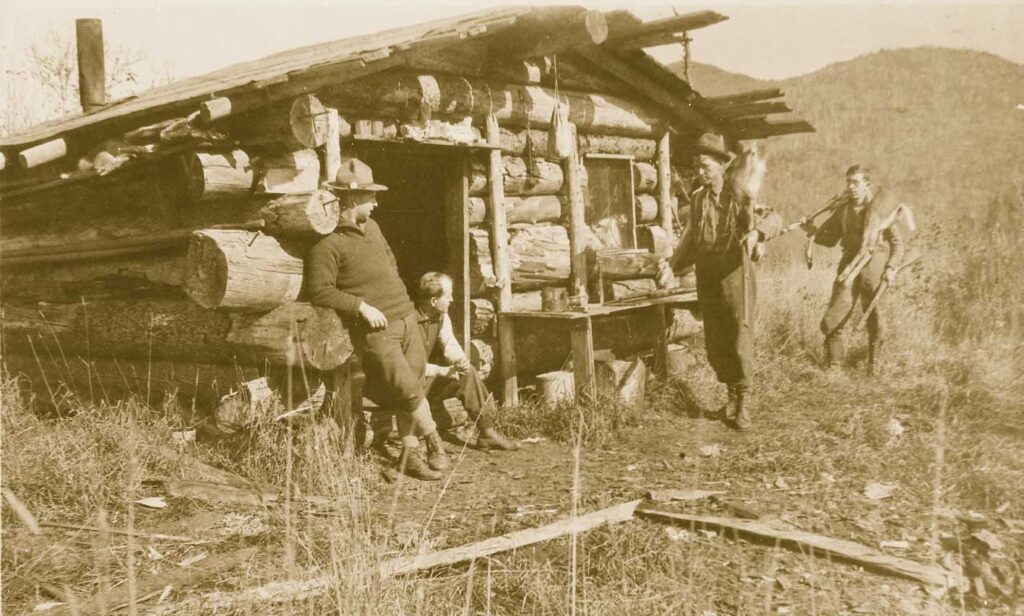

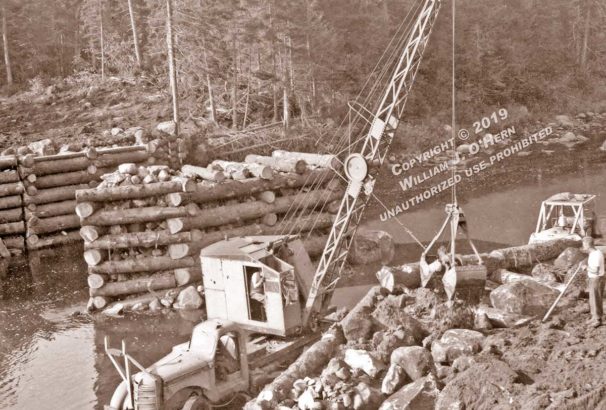

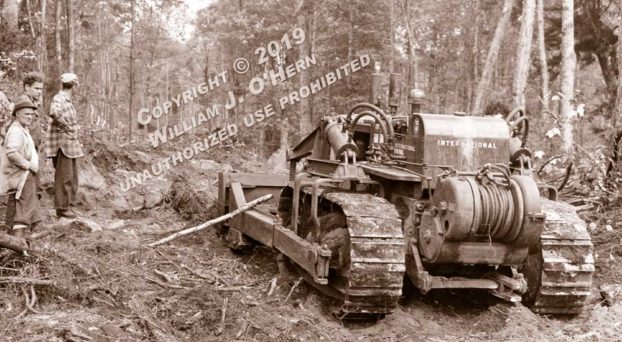

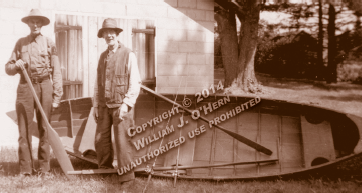

In 1873, by the time the women were working their way along the tributaries of the Hudson, Black and Moose rivers, the wilderness had not yet been opened by a system of roads. People were still sprinkled throughout the wilderness in isolated cabins and clustered in small settlements throughout the mountains. The majority of men supported themselves logging and guiding vacationing “sports,” hunters and anglers, who had most often been enamored by the writings of William H.H. Murray’s Adventures in the Wilderness in 1869. There are numerous references to Murray’s book in the letters written by the leaders of the four expedition groups, as well as to an earlier work, attributed to C. H. Burt in the Adirondack Bibliography, titled Opening of the Adirondacks, written in 1865.

Recognizing that my interest in the letters primarily centered about the events along the south branch of the Moose River and the Indian Plains, I contacted Barbara McMartin because of her enthusiastic interest in botany. Barbara was a keen observer of fungi, lichens, ferns, wild flowers really anything related to plant investigation and geology. There would be no one else more perfectly suited to take the material and do it justice. After exhaustive investigation and years of work, McMartin wrote to the “Lake of the Skies: The Benedicts in the Adirondacks”. Her book brought to light two never-before-published manuscripts that give new insight into the Adirondacks of the 19th century. One is a beautiful personal memoir that resonates with deep love for the wilderness; the other is an extraordinary tale of a harrowing women’s expedition that penetrates trackless forests in search of scientific knowledge. These very different works are by and about members of the Benedict family, who were involved in almost every aspect of the Adirondack region, from early surveys and land acquisition to the most cherished of summer vacations.

McMartin’s work is also a tribute to Benedict family members who had safeguarded the papers for years.

Miss Coulter (Electra) wrote: “Very soon after leaving the Lake [Pleasant], the great northern forests closed about us and all signs of habitation had disappeared, and, for once, we felt that our safety and perhaps our lives depended upon our own exertions and the care of our trusty guides.”

I often think of her description during my backpacks, which have taken me through the woodland where once part of the old Albany Road existed. The Albany Road was a blazed track during the time of the War of 1812. “French” Louie Seymour, the woodsman of the West Canadas and the Cedar Lakes, made his way over portions of the route on his treks from Speculator into that lake-speckled territory.

What follows is the June 6th, 1873 letter that describes the women’s wildwood camp made along the stream north of the Indian Plains. Without exception, the letter addressed to “My Dear Themis” tells of a tale of the not-so-simple life the small party endured together, told with grace and eloquence, from an early vacation the central Adirondacks.

For the rest of the story, please purchase “Moose River Plains Vol. 1” from your local book store or on Amazon.