Their notes, writings and photos are extremely helpful to me as I plan what I call historical bushwhacks-trips where I make use of the extensive personal papers, diaries, unpublished manuscripts, published articles, and photographs that generous relatives and friends of the men have offered me.

I admired these men for spending a lifetime searching and recording historical information. My adventures were thoroughly enriched because of their interest and research. I realized I should do something with their notes, pictures and out-of-print stories, to continue their work; I just didn’t know what-until an accident brought my thoughts together.

One winter night, as I twirled my swivel chair away from the computer to dart out to the kitchen for a handful of pretzel rods, I tripped over my cat, Rascal, who had curled up underfoot. I fell on the rug, “a double s over tea kettle,” as my grandmother used to say. As I went down, my arms went out to soften the fall, but my aim was misplaced. As I grabbed for the desktop I accidentally knocked over a pile of photographs that included photos from Rev. Byron-Curtiss’ albums and those Edward Blankman had loaned me. Mixed in with scattered vintage images was some correspondence from a 90-year-old occasional pen pal, Walt Hastings.

I cursed as I lay sprawled on the floor. Papers and photos were every- where. The hours I had taken to organize the pictures seemed like a huge loss. As I berated myself for not putting rubber bands around the various stacks, my eyes fixed on a letter from Walt. It was the last letter he ever sent me. I picked it up and began to read. In reminiscing about the history and happenings of the area in question . . . I dug into some old deeds and as far as I can determine, my Granddad arrived on the North Wilmurt scene in 1900, give or take a couple of years, some 30 years after the Reeds . . . arrived to settle at the mill.

I have no idea how long Granddad was at North Wilmurt before he met Addie [Hull].

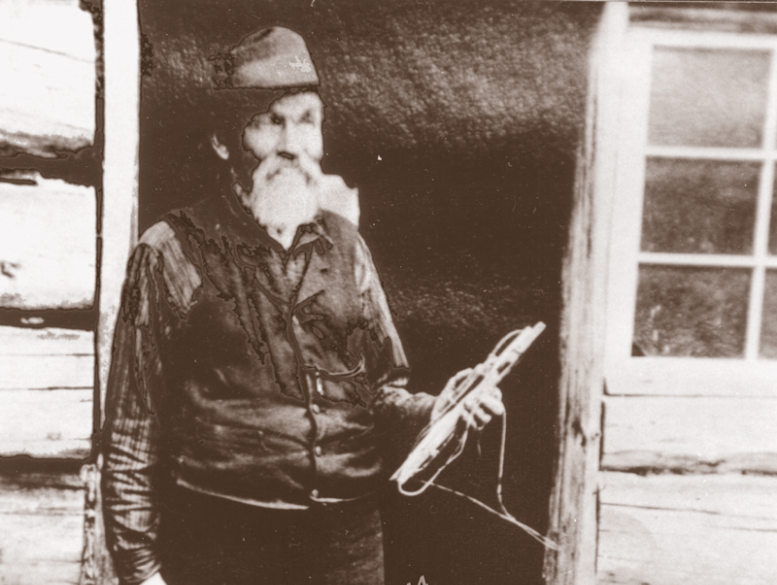

Addie was a good friend of Granddad’s. [As a result of his infantile paralysis] Addie’s method for get- ting from here to there was by crawling. He wore a pair of hip boots cut off at the feet (so the toes would not catch on roots and rock) and a pair of heavy rubber gloves similar to those worn by power company linemen. With his double barrel shotgun slung beneath his chest he would crawl on all fours, like an animal, to a favorite deer run to watch and wait. Because of his infirmity, balance was a problem and to prevent being toppled over from the “kick” of the gun, he would sit with his back against a tree. After bagging his deer, he would crawl back home to get help to retrieve the carcass. On a visit to his home in 1932, he told me many stories of his life and showed me 28 notches cut on the inside groove of the forepiece of his shotgun, each one representing a deer he had killed.

Walt’s letter went on, but Rascal interrupted my reading as he returned to the room. He now wanted the warm spot under the light. I watched him jump up and settle down. “Lucky cat,” I muttered.

As I fumbled over the photos, now totally out of any sequence or context, I began to look at them in a way I had never seen them before. Walt was still alive and kicking, but Byron-Curtiss and the others were all gone now. The pictures appeared ghostly on the floor, like faces in clouds, a mosaic of vanishing history blowing in the wind.

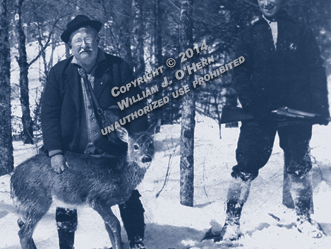

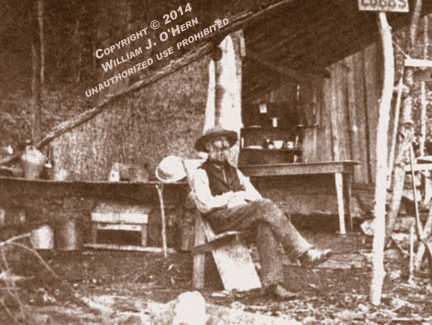

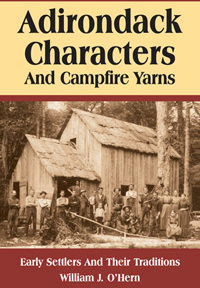

Instead of reorganizing I found myself randomly reviewing individual items. I focused on details I originally had overlooked. A new order was revealing itself. Pictures were no longer grouped according to whom I had received them from, but by what story they told. Pioneering natives, loggers, stage drivers, guides, well-to-do early camp owners could be categories. So, too, could moms and dads. Barefoot children, posing with rifles, standing by elders. Girls adorned in bows and ruffles with long curly locks, clutching bouquets of ferns. Boys dressed in bib overalls with a single pant strap buttoned at the waistband. Children rowing, carrying packbaskets or riding in them. Proud exhibits of fish hanging from stringers or singly from the ends of makeshift fishing poles. Gangs of loggers posed at their lumber camps. Clothes revealed whether it was warm summer, cool autumn, cold winter or buggy springtime.

For each, I had questions: What became of you, whatever your circumstances? Are any of you still alive? What families still live in the mountains? Do the settings in the pictures still look about the same, or has the landscape so changed that all that remains of those days are the ghosts of those who once roamed the land and the now-silent voices of the people frozen in a moment of time, calling out, “Hurry up and take the picture!”

I handled, sorted and filed one picture. I didn’t have a clue who the little boy in the blue-tinted photo was. I came across his picture in a copy of a 1912 edition of The Life and Adventures of Nat Foster: Trapper and Hunter of the Adirondacks. It had been placed inside the front cover. I believe it is Joseph Byron-Curtiss because his father, Rev. A.L. Byron-Curtiss, wrote the book. Tom Kilborne said it was one of twenty-seven books he inherited when he purchased the Reverend’s camp. A rubber stamp was used to identify where the book was stored. On several pages, a red and blue ink sign reads, “Nat Foster Lodge, North Lake. Adirondacks. P.O. Atwell, N.Y.”

I know the names of the two sporting writers standing on a beaver dam across Fall Stream in Piseco because someone penned the celebrities on the picture postcard. I estimate the picture to be close to a hundred years old, but from personal experience I can attest that paddling that stream is just as chal- lenging now as it would have been when the photo was taken.

Two photos showed interesting portraits of a young Byron-Curtiss and a fishing buddy. Someone scrawled with an old-fashioned pen-the type that required periodic dipping of the steel stylus into a jar of permanent ink- “Row, Row, Row.” Nothing there gives a clue to the person’s identity, but I showed it to one old-timer in Forestport who thinks it might be Ira Watkins, a turn-of-the-century guide who lived in Atwell. I figure there is a good chance he is right. There is also a good chance that every natural setting shown in the photographs could be rediscovered today: The landscape of the headwaters has changed very little in the last one hundred years.

Mortimer Norton once said that outdoorsmen tend to overlook significant features of the North Woods-“its mountain meadows and wild flowers.” Lloyd Blankman would have added, “and the lore of the mountains as well as the Adirondack characters.”

Lloyd’s essays colorfully recreate life in the Adirondack Mountains in firsthand accounts. They contain little formal history, because unlike the works of scholars who sift and arrange facts into understandable sums and patterns, Lloyd’s stories are the stuff of history before it is worked by the hands of historians.

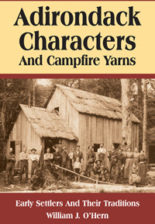

I knew Lloyd had dreamed of organizing his newspaper and magazine arti- cles, along with the published and unpublished works of Harvey Dunham and Mortimer Norton, into a book. It was to be titled “Adirondack Characters,” after the banner of his column in The Courier, Clinton, New York’s hometown newspaper.

A similar book of campfire yarns and Adirondack characters, which would include those authors themselves, was taking shape in my mind. It wasn’t long before I was making further inquiries to find relatives, additional materials, and permission to use them.

In the summer of 2002 I visited Lloyd Blankman’s son Edward and talked with him about the project. I quietly suggested to Ed that I would like to finish his father’s dream, by way of incorporating material I had collected that bore a likeness to stories told by Lloyd. I wanted to produce a book that told the stories of early settlers-stories that originated from the West Canada and Black River headwaters.

Almost immediately Ed replied, “You have my permission to use all the material my father gathered and was given permission to use.” He disappeared into another room, coming back shortly with two boxes containing additional treasures of antiquity.

“You’re tapped into an interest of mine,” he said. “My father enjoyed gathering fresh and authentic material for his lectures. Yes, go ahead. As a matter of fact I would love to write an introduction.”

Funny how things go. If Rascal had not been underfoot, the idea to assemble these early Adirondack folklorists’ anecdotes and photographs into a book might never have crystallized. I’ll say thanks now, Rascal, because I certainly didn’t then.

My other colleagues in the preparation of this book are Lloyd Blankman, Rev. A.L. Byron-Curtiss, Harvey L. Dunham, Thomas C. O’Donnell, and Mortimer Norton. They were all woodsmen at heart, their haunt the south- western Adirondacks. There they fished and hunted, and were “regulars” sharing their lives with the natives of the region. The writers are long deceased, but their stories, articles and memories about a variety of Adiron- dack characters, their vocations and their uniquely Adirondack way of life live on. This book weaves their works together with mine to present a glimpse of Adirondack pioneer life, an artifact that can provide future readers with an appreciation for a plain-spoken way of writing and some good old campfire yarns.

William J. O’Hern, March 2004