“Mon” Lost in the Woods

An Excerpt from Life at a North Woods Lumber Camp

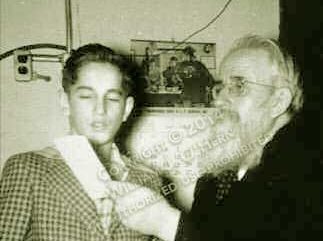

Around eight o’clock one October evening, before he turned in, Old Pat Moran laid down the last stick of shavings for the morning fire and went down to the stable for a final time thinking something might have been overlooked. While closing the double doors he suddenly stopped dead in his tracks when a faint sound of a rifle shot reached his ears. The old warrior suddenly sprang into action and rushed to our house, his hand trembling as he shook his cane upon finding Father.

“There’s a mon lost, George! I hear’n his gun!”

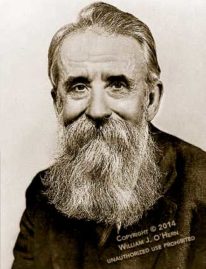

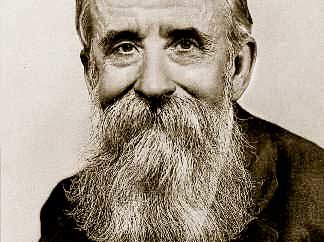

Photo courtesy of JohnDonahue

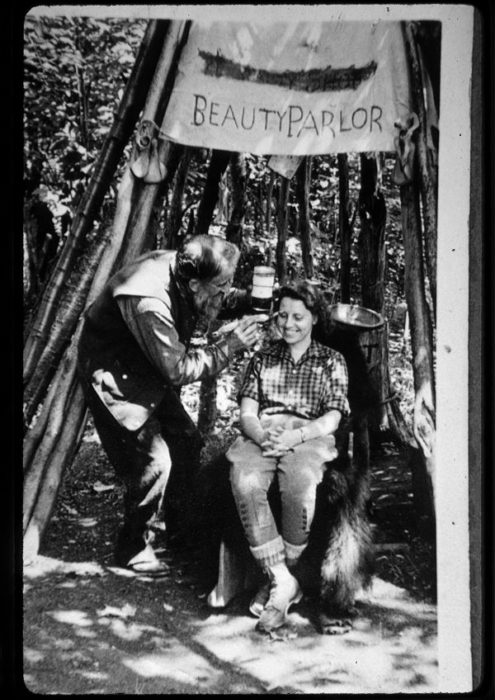

In the early days of logging, man power and horses were the only power used.

A gunshot at night was a sure sign that someone out in the woods needed help. The household was suddenly electrified at the news, as was the lumber shanty below the house as quickly as Father could get down with the news.

Presently the jacks gathered on our porch. Father directed the searchers to concentrate on the east and north sides, reasoning properly that men could not easily get lost in the land to the south or to the west.

Ben Watson, who this season had been taken off the list of sawyers and made a swamper, was for everybody setting off in different directions, the women folks of course excepted. He was certain that by climbing trees and yelling at the top of our voices someone would be sure to make con- tact with whoever was lost out there in the night. Father suggested that it would be best to first fire a salvo from our double-barrel shotgun. The roar hardly died away when a faint report came from afar off, easterly.

“They hear’n us!” Jut Gannon declared.

Everybody agreed except my brother Fred.“How do you know?” he asked.“Maybe he didn’t hear you at all, Pa.”

At that point Mother broke in, “What direction did it come from?”

Discussion indicated that the report came from several directions. The men decided to strike out in pairs, in various directions. Emory Lewis would carry Old Bet on his shoulder for future soundings.

Just as the rescuers began to filter out, Dave Wright dashed in asking if any- body had seen his old man, who had gone out hunting birds that morning in the region east of the O’Donnellses.

My emotions were not unmixed. I harbored certain prejudices toward Old Man Wright. He was a short, stocky man, proud of his bulging paunch. Mutton- chop whiskers without a mustache adorned his face.

All the kids called him “Pussy.” Pussy liked to tease us in a not-so-friendly way. Suddenly another report of gunfire reached us.“That’s old Bet,” Fred declared.

“It’s coming from over at the Cedar Swamp northeast.”

Then came another and another followed by an answering shot. Within min- utes, from various directions there began to be heard the calls of our men, who, from tops of trees, would be cupping their mouths with their hands and letting go with a hair-raising “Hoo-oo-oo-oo!”

Meantime Dave Wright was declaring, “Pop was never lost before.”

“Howjuh know? Ever ask him?” My brother wanted to know.

Presently another shot was heard. Evidently impatient, Pussy was going away from the rescuers.

“Now he’s getting rattled,” declared Father. “He’ll never stay in one place and let the men

come to him. No. He’s got to dash around and find them!” Ten minutes later more shots showed that he was moving farther away and veering to the south. Bert Stahl and Emory Lewis had gone across the river and struck into the timber when they caught the report of

Pussy’s firearm. The two soon closed in and at long last had their man, safe and sound, back at our camp.