The following are two of Smith’s hermit stories based on events from … experiences in the Cold River country … and his life with Noah John Rondeau.

The Hermit and Us – Our Adirondack Adventures with Noah John Rondeau

Smith’s Hermit Stories

An excerpt from “The Hermit and Us”, Starting on page 274

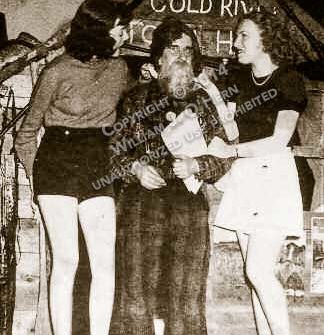

“Noah sure was a magnet,” Richard Smith underscored.

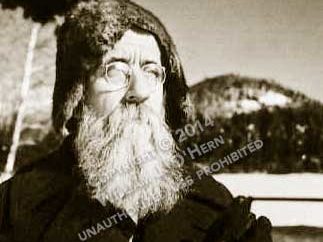

He attracted people from all walks of life to Cold River. I often thought, when he was feeling a mite lonesome following months of having no human contact, that he would step up the power [of the “magnet”] and before long someone would show up, whether it be a hunter, a fisherman or just a hiker or mountain climber stopping by to say hello.

I know how often I would get an overpowering urge to visit him, and as I neared the City my often dragging feet would have more spring the last few miles, anticipating the joy I would soon feel in the presence of my most unforgettable character. Wishes were fulfilled here.

The following are two of Smith’s stories based on events from Smith’s real-life experiences in the Cold River country, his memories—individual and outdoorsy—and his life with Noah John Rondeau. These stories paint a vivid picture of just what it was that made Cold River life an amazing experience.

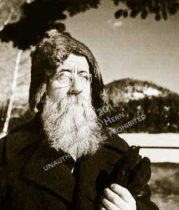

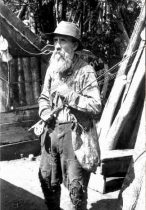

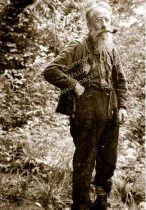

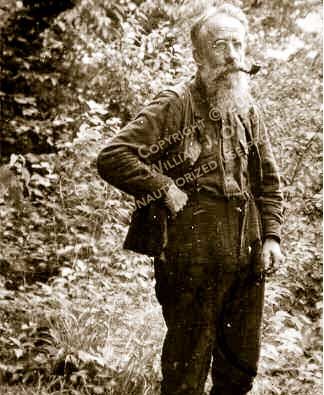

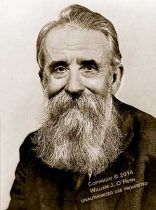

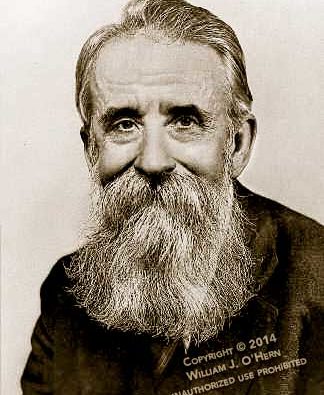

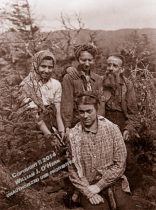

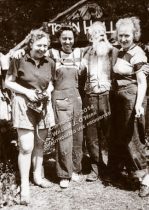

Courtesy of Richard J. Smith from Noah’s photo album

By living a hermit’s life, “Old Whiskers” realized a degree of freedom many of us only dream about.

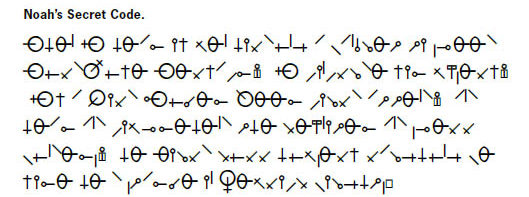

Smith related that to mark special occasions, Noah would bestow a dol-lop of scotch from his Trophy Bottle upon any deer hunter companion who bagged a buck, then record the event in his hieroglyphic code on a piece of white adhesive tape affixed to the side of the long-necked whiskey bottle

Smith’s stories started when he graduated from high school in 1939 and put down roots in the mountains, first in a cobbled-together camp in the headwaters of the Chubb River and later in a cabin near Duck Hole, headwaters of Cold River. From it, Smith had almost constant access to his mentor, Noah Rondeau. The diverse tales are sometimes related in high spirits, sometimes in a matter-of-fact tone, and occasionally in a reflective way. The real life stories explore Smith’s life with Noah in the days of the old-time woodsmen.

A particular fond memory Smith always carried was of a special bottle of spirits the hermit kept at the Hermitage. Smith’s remembrance of the booze jug and its hidden location at the Mammoth Graveyard—Rondeau’s secret place where he stashed valuables in Ouluska Pass—set me on several unsuccessful bushwhack to find the hidden collection of galvanized garbage cans. Noah collected them from former Cold River side camps when the CCC pulled out, and found them perfect for storage of many items.

Smith related that to mark special occasions, Noah would bestow a dol-lop of scotch from his Trophy Bottle upon any deer hunter companion who bagged a buck, then record the event in his hieroglyphic code on a piece of white adhesive tape affixed to the side of the long-necked whiskey bottle.

When I hear of men holding a banquet to speed “Wild Life Welfare,” I conclude for myself, “If a Cold River Deer could attend, and hear and comprehend the keynoter and spell binders, he would kill himself laughing before he’d starve on Hemlock boughs. —NJR in reply to Ranger Toomey telling Noah about efforts of sportsmen’s clubs feeding deer.