The Hermits Countdown to Christmas tells of the unusual life of one man who proved that with determination he could live in his own individualistic way.

Adirondack Hermit Noah John Rondeau’s December 1943 Daily Countdown to Christmas and the New Year

This month-long daily posting I’m calling “Adirondack Hermit Noah John Rondeau’s December 1943 Daily Countdown to Christmas and the New Year” tells of the unusual life of one man who distanced himself from civilization and proved that with determination he could go into the mountains to trap, hunt, and fish, and live in his own individualistic way on a parcel of private property he had been given permission to occupy. Not only did he do that off and on for thirty-seven years, but he also demonstrated something else that is very significant.

Noah John Rondeau demonstrated in his unorthodox journey that the spirit of personal adventure outside the conventional walls of home and employment was not yet dead, that opportunities for adventurous living on one’s own terms could still be found.

It’s refreshing to think of the rare individuals who have followed such unconventional paths. Just knowing Rondeau chose to live by and follow a very simple, basic, and honest code is doubly refreshing and encouraging to throngs of men and women who have a touch of wilderness within them. The hermit of Cold River’s story is the story of the Adirondacks themselves. Although he abandoned his hermitage in 1950, the site continues to draw the curious as they themselves seek to experience a bit of Rondeau’s world. And why? Backpackers say the trip by foot over miles of rough trail blends the feeling of the utterly wild, uninhabited setting of an earlier era with their modern-day adventures. Some hikers say their trek is nostalgic, knowing they are following in the beloved hermit’s footsteps.

Noah John Rondeau’s daily story demonstrates that the frontier boundaries of courage and romance still exist within those souls who are willing to venture forth. One has only to choose asetting for the drama. Rondeau chose his in an isolated, backwoods setting in 1913. People like him no longer exist any more than do Jim Bridger and Sarah Bayliss Royce. Your “frontier wilderness” may be in your home’s immediate surroundings, in a state or national park or curled up in an easy chair with a book, but if your mind is an imaginative one, if your heart seeks the unexplored, the setting does not matter. Your life will be an adventure.

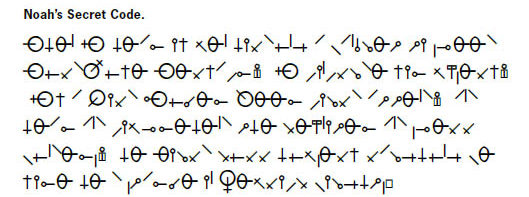

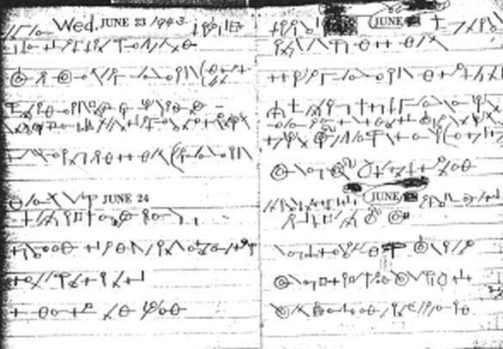

The Secret Code

How often have folks wondered what Noah did from day to day? And how many of us wondered what he recorded in his cryptic code one person described as the “scratchings of an inebriated hen?’ I for one have. Look at the example of how he documented each day throughout 1943 in code. Why did he invent and write in this manner? Were there things to hide? Well, his cryptic code was deciphered in the early 1990s by David Green. Since the breaking of the code many of the hermit’s yearly diaries have been converted to English.

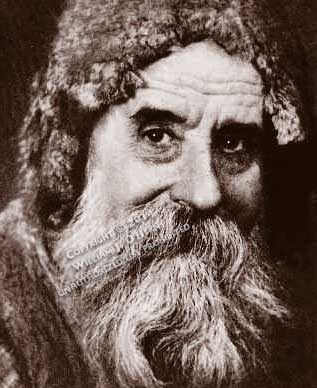

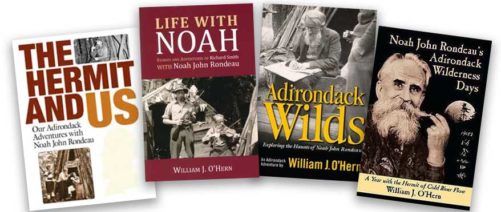

William “Jay” O’Hern has written extensively about the life of Joah John Rodeau, the hermit of the north country.

The four books shown tell stories about Rondeau. Each different and all enriched with rare photos. And YES there is that much different information about the man. In fact, a fifth and sixth book have been written and graphically designed, but remain unprinted.

One has to do with attorney Jay Gregory and doctor’s C.V. Latimer Sr. and Jr. It is to their credit Rondeau was able to get along in the wilds as long as he did. The second story covers his life from the year (1950) he left the woods to the day he passed in 1967.

The Gregory – Latimer book is based on a selection of snapshots from the hundreds of pictures given to me by my dear older friend “CV” Latimer Jr., M.D. The sixth storybook covers Rondeau’s very interesting final seventeen years. It too includes remembrances of people he interacted with throughout that time. The lack of shekels prevents printing.

Noah’s activies up to today, December 7, 1943.

Tue. November 30,1943.

Written at Handsome View. Much Sunshine, Few Clouds. I shoot mustache off Coon. I eat Coon. Deer Season Close Tonight.I go for walk to Seward Pond outlet and bring in five mink traps. A weasel call at the TownHall.

Wed. December 1, 1943

Sun Shine at Pyramid of Giza and Beauty Parlor wigwam. I see a little Buck within 100 ft. from Town Hall and two Deer Big near Dam. I take a walk in the woods. I call at fox pills. And I read READER’S DIGEST and play violin.

Thur. December 2.

Mild and Somber. Big Dam. John Brown put to death 1858. I saw 2 Deer at river dam.

Fri. December 3.

Very gloomy and mild. Written At Hall of Records. I read and fiddle.I eat Coon.

Sat. December 4.

Gloomy and Mild. At Beauty Parlor. I eat Slam Bang. Moon 1st quarter 7:03 AM.

Sunday, December 5.

Sunshine and Cool Breeze. At Big Dam. I read Readers Digest.Mars is in Opposition.

Monday, December 6.

Gloomy and Cool. PM Blizzard. At Hall of Records, Cold River. I wash 3 Hand Kerchiefs and a few other pieces. I call at Quack (Richard Smith’s) Fox Pills. I cut my Hair and trim my Beard; getting ready for Santa Claus. I take a Random Scoot in the woods in afternoon Blizzard. I skin the Deer’s fore-quarters while they are relaxed from frost. I read and write.

December 7.

4 Inches Snow Last Night. Cool and Somber. At Metropolis Beauty Parlor. Beard Trim and 1 Haircut. All Ready Santa.