BY TED ABER AND STELLA KING

The following is Part 1 of a story by Ted Aber and Stella King that first appeared in Tales From an Adirondack County (Prospect Books, 1981). It appears here with permission of Rob Igoe, president and owner of North Country Books. Aber and King were devout local historians. It is to their effort that so much early Hamilton County first-person history has been documented. —William J. O’Hern

Spring log drives were once common sights throughout the Adirondack Mountains. Today they live on safely preserved in Indian Lake’s museum.

Into the small hotel in a village in St. Lawrence County walked a short, unprepossessing-looking man. Lifting his unshaven face to the desk clerk, he asked for a room for the night.

Quickly, the clerk surveyed the undesirable – his unbuckled overshoes, unkempt woodsmen’s clothing, and the characteristic chew of tobacco that wadded his cheek. The hotelman was sorry; there wasn’t a room in the house.

Wordlessly, the small man rocked back on his heels while reaching into his pocket and drawing out a roll of bills that obviously totaled into the thousands. Thoughtfully, he thumbed the hundred-dollar notes.

The desk clerk suddenly remembered any one of several accommodations that might be at this honored guest’s disposal. The newly arrived was hurriedly shown to his room. The experience was typical. The man was Lumberman Ernie Brooks from Newton’s Corners, on a horse-buying mission to the northern part of the state.

Ernie, who was born at Indian Lake of Joel and Helen Morehouse Brooks, was a woodsman from the start. In a period when local lumbering was in its heyday in the Adirondacks, Ernie helped to give it dignity and color. He and his brothers, Ed and Clarence, lumbered for years at Indian Lake, Ernie and Ed joining forces to form the Brooks Brothers Lumber Company there. Not content with lumbering alone, Ernie was a hotelman on the side.

Up at Indian Lake, Ernie was married to Myra O’Kane. When she died after bearing him four children, he moved his family down to Newton’s Corners in the Town of Lake Pleasant and later married Nathan and Mary Satterlee Page’s daughter, Nora. Together, they ran the old Brooks Hotel south of the four corners and raised a family of five.

age was once a booming community with numerous hotels.

Ernie’s reputation as a lumberman was a good one. None worked his men harder. None offered better pay. A man knew, when he signed with Brooks, that he was to maintain an active life throughout the long months in the mountains.

There was a reason. One winter, over on Sacandaga Lake, Ernie misjudged the weather and, before he could get his logs banked, the spring thaw set in. The logs lay on the ground throughout the following summer and the family lacked the income that was so badly needed. It was a bitter lesson that Ernie never forgot. After that, he worked himself and his men with fury to be sure always to make the drive on time.

Selah Page worked for Ernie in the winter of 1916 at Coon Creek near the third bridge on the road to Wells.

“We used to pull the horses out at 2:00 AM and wouldn’t see camp until dark. I’ll give Ernie credit, though. He was out with the head team and came back with the hind team each day. And he paid good money. But the work was just too hard. I said if I can’t make a living easier than that, I’m going to starve. After that, I did freighting for the camps but never lumbered again.”

One evening, a call came for Dr. Joseph Head to go to the Brooks camp to treat a sick lumberjack. By the time he had bounced over the rough woods roads to reach his destination, it was the middle of the night. To his amazement, the men were already at breakfast. Ernie himself had appeared at midnight for his morning chow.

“Dr. Head sat relaxing over a cup of strong hot coffee. Nearby sat Jerry Murphy, a rugged lumberjack known for the quality of his work.

“Yes sir, I’m going to quit,” Murphy told the physician. “Ernie promised me a full-time job and we’re sleeping a couple of hours every night. That’s no full-time job. I’m through.”

Each day, the clocks at camp were set a few minutes further ahead, so the men would not complain too bitterly about their early rising hour. One winter night, the men had just completed drawing logs and were wolfing down their evening meal. It was 9 o’clock in the evening but the clock read 12.

Allie O’Kane of Indian Lake sat eating with his boss. “Ernie,” he drawled, “if you don’t change that clock pretty soon, it’s going to be Fourth of July before the snow goes off.”

Ernie could laugh with the others, but his firm discipline never faltered.

Once, while lumbering at Cannon Brook, the lumberman came out of the woods and procured a rooster. It would start crowing daily at 4:00 AM. Ernie called it his alarm clock. Thoroughly annoyed after several days’ repetition of this newly-found reveille, the boys decided that something must be done. The next day, the lifeless rooster hung on the knob of the bunkhouse door. Ernie was silent, but soon returned with a second rooster.

“The one who kills that bird is fired,” he announced.

The rooster remained alive.

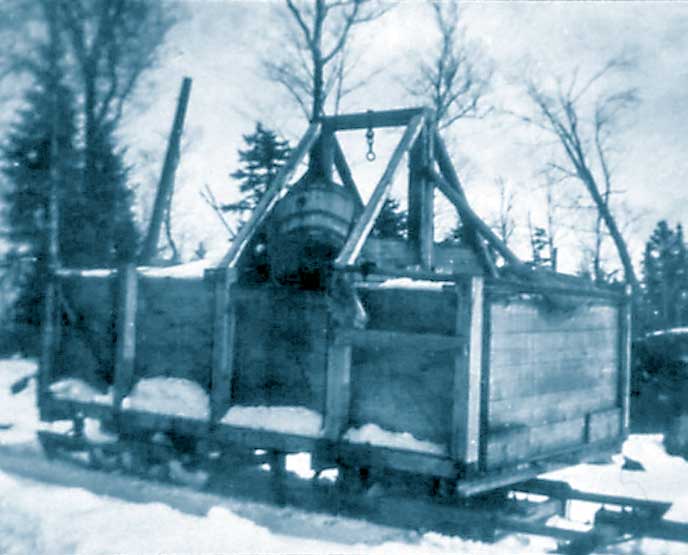

Sprinkler sleigh used to harden winter logging roads.

To be continued. Part 2 of this story will be featured in the next issue.