The wolf-shooting logger-woman Mary Andreason’s story was one of safety, forestry, and the economic and social life of America.

A Look Back In Time

Mary Andreason, Pioneer, Lumberjill and Wolf Shooter

An article printed in “The Northern Logger “, October 2022

Among the logging-related articles to appear in the March 1952 issue of The Lumber Camp News was “Pioneer Woman Shot Wolves, Worked at Logging.” Frank A. Reed, senior editor-publisher, wrote that the story first “appeared in the November 17, 1897, Potter County Journal.” The catchy title was sure to attract the attention of the magazine’s readers. Reed said, it “paints a picture of the early days along Kettle Creek” and tells about the pluck and courage it took for a woman to live on the frontier.

This old-time story, set in the woods of Pennsylvania, is characteristic of the breadth of material that appeared in Rev. Reed’s logging publication, along with articles about lumbering operations, used and new machinery and equipment for sale, and reprints from logging and farming periodicals such as Maine’s Portland Press Herald, Heard’s Dairyman, Pennsylvania Forests and Waters, and the Canadian Pulp and Paper Association. For example, “Old Timers’ Notes” profiled older logging jobbers, and there were informational columns by writers from Tennessee, Wisconsin, Michigan, California, and various forestry colleges around the country.

In addition to his recapturing the then 55-year-old event, the editor made an announcement that by the July 1952 edition, the magazine would appear under its new name, The Northeastern Logger. This was an exciting time for Reed, who almost single-handedly began The Lumber Camp News in 1939. He announced that there would be a staff of eight people from various parts of the Northeast who would carry on the program of publishing and that the editorial office would remain in Old Forge, NY. The magazine’s name change was made so it could more completely cover the broader scope of material and service. Retired editor Thomas C. O’Donnell offered changes to improve the appearance and layout.

The wolf-shooting logger-woman story was perhaps included because of a new thrust to include a wide range of news coverage such as safety, forestry, the economic and social life of America, fire control, logging operations, education, a Christian column call the “Sky Pilot Page” and what became a popular “Adventures of Uncle Hatchet” tall tale column, to name a few.

The woman is Mrs. Mary Andreason, and she is the widow of the former secretary to the famous Ole Bull, a Norwegian who formed the colony of Oleona in Potter County, Pennsylvania. Mrs. Andreason (then Mrs. French) was a widow when Andreason met her. But don’t picture a genteel and soft-spoken lass who stayed home cooking, sewing, and spinning when you think of Mary French Andreason.

She was first married to a settler and trapper named French when Potter County was pure wilderness. Today she says her bones ache with rheumatism, perhaps due to the physical demands of her early pioneer experiences. She hunted and trapped at her first husband’s side. It is said that during one winter, Mrs. French, unaided, trapped 65 gray wolves, knocking them in the head with a hatchet that she always carried on a belt around her waist.

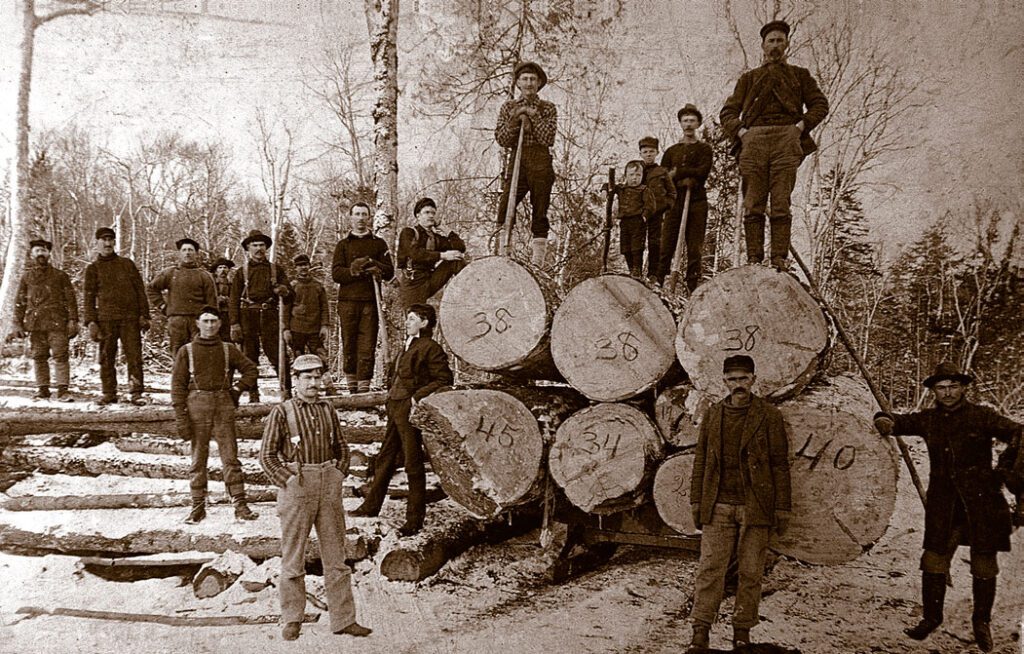

Along with hunting and trapping, Mrs. French is notable because she went with her husband and a crew of men to drive logs on Kettle Creek. With pike pole or canthook, this powerful woman waded the streams with the men, whirling a derelict log into the stream or breaking a jam at the creek’s bend.

Driving logs is so dangerous a business that plenty of men won’t risk it, yet Mrs. French took on the job more than one spring, and earned from six to eight dollars a day. Even now, at 85, she mentions with considerable pride the time when she was young and strong enough to pitch logs in Kettle Creek. Mrs. French was widowed in 1850, and was still quite young when 74 Ole Bull, a Norwegian violinist, declared to several hundred hopeful immigrants, “We are to found a New Norway, consecrated to liberty, baptized with independence and protected by the Union’s mighty flag.” Ole Bull and his followers came to Potter County and took up a 12,000-acre tract.

The arrival of the Norwegians made life a bit easier for Mrs. French. She was soon employed as a cook at the Norwegian headquarters, where she met and married Henry Andreason, one of Ole Bull’s immigrants who had come along to manage the affairs of the Oleana colony.

Despite the easier life, Mrs. Andreason was not crazy about the colonists. She says they danced and carried on “too high” for her. Often the Norwegians would dance all night to the tune of a squeaky fiddle when they should have been resting for their next day’s work, clearing new ground for their little farms.

Mrs. Andreason says the best and most exciting time of her life was the first years she lived in Potter County. There were unimaginably large herds of deer and elk; panthers prowled and growled and wolves filled the night with their howls.

Mrs. Andreason was an expert rifle shot and had slain scores of black bears, wildcats and deer. She specialized in wolves, however, because the bounty was large enough to make it profitable to hunt them.

Mrs. Andreason was once delayed when she was heading home on a footpath along Kettle Creek. It grew dark. She heard wolves approaching. She says she figured they were on her trail, so she strapped her rifle to her back and climbed a hemlock tree, knowing that if she could get a dozen feet above ground she would be safe from the wolves’ sharp teeth and claws.

Later in life, Mary Andreason enjoyed sharing her hardscrabble life on the frontier. In less than ten minutes the pack of wolves surrounded the tree where she had taken refuge. She could see their eyes shimmering in the darkness; she shot them one by one as fast as she could reload.

She wasn’t far from home, and the sound of the repeated rifle shots soon brought her husband. He came bearing a rifle in one hand and a flaming torch in the other. The fire frightened away the few remaining wolves.

Mrs. Andreason gathered up the dead wolves at the foot of the tree – not as a souvenir of her experience, but as a reward for her night’s work.

After her husband died, Mrs. Andreason continued to live with her son on a small farm in Potter Colony.

Lumbermen and women were colorful characters, and they enjoyed remembering one another in the often exaggerated tales they recounted, but Mary Andreason’s tale needs no embroidering. These were the kind of memories Frank A. Reed kept alive during the years he ministered to the ‘jacks who lived in the lumber camps – camps he often walked many miles through deep, trackless forests to reach. It is to Reed’s credit that they live on to this day in The Northern Logger’s archives in Old Forge, NY.

Photo COURTESY PAT PAYNE

Photo COURTESY PAT PAYNE