The Linn Tractor, with its mechanized track, played a huge part in ushering logging into a new and much more efficient era.

A Look Back In Time

Logging’s Connection with the Linn Tractor

An article printed in “The Northern Logger “, July 2022

The Linn tractor played a huge part in ushering logging into a new and much more efficient era. In this article, “Adirondack Logging,” Rev. Frank Reed meticulously explained the usefulness of the Linn tractors – the new-kid-on-the-block mechanized track machines that replaced old-style horse logging. Reed’s dissertation did not say how important the Linn tractor was to the growth of the paper industry in northern New York. Nor did he mention the far-sighted industrial statesman, G.H.P. Gould, who allowed his superintendent, John B. Todd, to purchase the experimental machinery that became so important to the Gould Paper Company’s success.

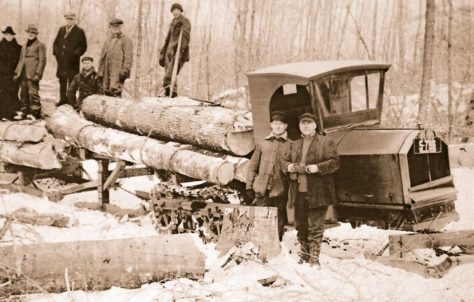

H.H. Linn (far right) by one of his early tractors. Circa. 1918-19

As a young boy working in his father’s logging business, an Upstate New York logger named Leigh Portner recognized the importance of sound performing machinery. As an adult he foresaw the benefit of restoring to working condition two Linn tractors his father once used. Today, at 87, Leigh continues to operate Portner Lumber Company and Sawmill. One of his pleasures is to show off his favorite Linn tractor. I asked Leigh to write about what he has learned and what he imparts to people who inquire about the line of now-antique Linn machinery.

Portner remembered this:

“The first Linn tractors used in the Adirondacks were sold to the Brooklyn Cooperage Co. and John E. Johnson of Port Leyden, N.Y. These early tractors came with a fifth-wheel trailer log sleigh, but the trailer did not work out well. One of the larger companies to use the Linns was the Gould Paper Company of Lyons Falls, N.Y.

Gould bought twelve tractors and a number of log sleighs to go with them. Each tractor cost about $5,000 and came with thirty sleighs each. The reason each tractor had three sets of ten sleighs, costing about $160.00 per set, was because of the high degree of breakdowns. Haul-back roads were rough. Between the sleigh’s vast weight, the steep grade, and uneven jarring terrain, the equipment took a beating. Broken runners and other parts were a continuous problem. The blacksmith was responsible for constant and necessary inspection and maintenance. They cycled the sleighs: while one set of ten was being loaded, another set was being checked by the blacksmith for breakage, and another set of ten was being unloaded at the landing.

Two early Linn tractors.

Gould bought some larger six-cylinder model Linns in 1926. Each sleigh, once loaded, averaged about ten tons. The haul roads were kept well-iced with sprinkler wagons. On a twelve-mile-long road they used four sprinklers. A sprinkler was built onto a Linn with a trailer sprinkler tank in tow.

Travel on the steep hills was controlled by the sand hill man. His job was to ensure the tractor driver hauling the loaded sleds had a safe descent. He’d shovel little piles of hot sand and scatter straw at regular distances along the sloping snow road to keep the loads from jackknifing on the downgrade. The stuff slowed the tracks on the descent so that the engine would have to pull hard to get the load to the bottom. The sand hill man kept a fire in the sand pit because only hot sand would stick to the sleigh runners to slow them down. Gould declared that with a properly iced road, the Linns could pull forty cords up a five-percent grade.

Along with the tractor driver was a whistle punk. He was there to warn the driver if the bull-bows broke and the log load began to buckle. If any of that happened, the driver would have the time of his life exhibiting a bit of fancy steering on a wild ride downhill, trying to get to the bottom with his life intact.

At a logging camp called “Camp 7” at Ice Cave Mountain, the tractors were kept in a steam-heated garage. Between this camp and a similar garage at Camp 9, on the river, they kept two mechanics and a greaser busy doing maintenance. All the tractors were greased every night. When the temperatures reached forty degrees below zero, they would have to disconnect the fan belts and cover the radiators to keep them from freezing.

A Linn tractor pulls into camp 7 on it way to the Moose River Landing.

The Linn tractors were started and out by 4:30 in the morning. They tried to make three loaded trips per day to the Moose River landing with each tractor. Each Linn had a driver and a whistle punk who checked the toggle chains on big loads. Most of the drivers would pit the tractor out of gear on the big hill that went down to the river, and let it rattle full bore. That way they wouldn’t pile up the loads on the way down. The tractor drivers of the 1920s and ’30s got $4.00 per day, while laborers got only $1.00 per day and board.

The riverbanks were about twenty feet high in this area. The drivers would dump the first loads from the bank into the river, and as more logs came in they would build up a log bridge across the river. They’d freeze the bridge with snow and then build another bridge about 100 feet beyond the first one. As the bridges were completed, the tractors would drive out on them and fill in between the two bridges with more logs. When the ice went out in the spring and the drive started, the logs would roll right along from the landing in the woods to the pulp mill at Lyons Falls.

My experience with Linns started when I was fourteen years old and my dad let me drive our Linn with a large load of hardwood logs on it. My dad, Ernest Portner, had purchased the timber rights on a large wood lot in 1938. It was the site of a Civilian Conservation Corps camp beyond Hanifin Corners in Empyville, New York. The camp was still active. Most of the men were African-Americans. He bought it from the State of New York with a successful bid. These woods had never been cut, and the yellow birch and hard maple trees were thirty and forty inches on the stump. All the supplies were hauled in to camp with the Linn, Dad had a camp built for the men and a horse barn for the team. We had about twelve men working on this job, and we used the Linn to haul out to the truck landing, which was about five miles. The snow was four feet deep that first winter, and sometimes the temperature was thirty below. But the Linn would always start with gas in the primer cups and a few good pulls on the crank.

My father worked in those woods three winters and four summers. Though the years Dad had six Linn tractors: three 4-cylinder and three 6–cylinder. All were either scrapped or sold, except the 126 4-cylinder. That was used in the winter of 1964 to haul some big pine out to the truck landing. Then it sat out back of our sawmill until 2009, when I decided to restore it. I also have the 1921 Emporium No. 3 I mentioned earlier, and a 1928 6- cylinder. Both need restoration. In 2018 I took my restored 1926 Linn to the New York State Woodsmen’s Field Days at Boonville, New York. It made a quite a hit with the crowd.

At one time, my father also had the county snow plowing contract for snow removal on about twenty miles of road. We had three F.W.D. trucks and a 6-cylinder Linn with a V-plow and double sixteen-foot wings. With the dump box full of fifteen tons of ballast, he could plow six and eight feet of hardpacked snow with no problem. Our Linns never needed much repair work, as we kept them in good mechanical condition. They did not go fast, but they’d go through any conditions.

After the1950s, the Linns went by the wayside as the new skidders and other machines came out. They were last used in the Adirondacks in the late1950s, and then scrapped.

Other loggers and sawmill men throughout the state and nation also used Linn tractors from the 1930s through the 1950s. Many of the jobbers working for such outfits as Gould Paper Company, Finch Pruyn, and International Paper used Linns, as well as many smaller companies. The Linn Tractors were popular and well-regarded machines amongst the loggers and lumbermen of New York State.”