Logger Harvey Carr thought to save Adirondack hermit Noah John Rondeau’s cabin from the bulldozer.

An article printed in “The Northern Logger “, November 2022

Noah John Rondeau was a hermit who lived alone in the woods of the Cold River basin in New York’s Adirondack Mountains. There he built his own hermitage and lived for 30 years in two small cabins and some wigwams. He had decided to become a hermit, he said, to escape “the slavery of industrialism.” After a windstorm wrecked his camp in 1950, Rondeau moved out of the woods and spent the last 17 years of his life living as a boarder.

When the abandoned residence was about to be bulldozed in 1959 to complete a contract cutting, local logger Harvey Carr thought it was a shame that this piece of Rondeau’s life would be destroyed. With some help from Eleanor and Monty Webb, owners of The Cliff Hanger Resort in Blue Mountain Lake, along with renewed interest in the hermit’s life from the media, the curator of Adirondack Museum (now known as The Adirondack Experience), Dr. Bruce Inverarity, became convinced that a remaining cabin was worth saving. He granted Carr permission to transport it to the museum’s grounds.

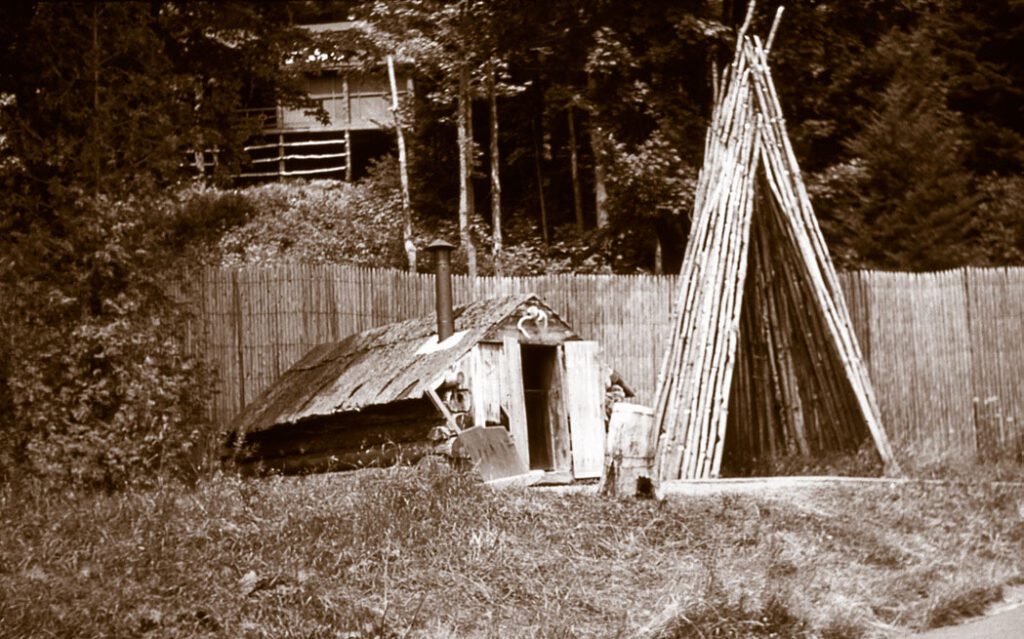

The cabin was made of notched hemlock logs with a bark-covered roof and had a built-in log bunk and stove.

As Eleanor Webb recalls, as soon as permission from Inverarity was granted, Carr took on the arduous job of moving the cabin to the museum. “He painstakingly numbered each log, each board, and each item, carefully dismantled it all, and prepared it for travel the long way out over the rough logging road. He was almost defeated trying to get some help and some way of transportation out [to the museum]. I think one man [Paul Crofut] helped him after he had gotten the consent of the museum to send a truck. Then Harvey put it all carefully together again on the farthest-out perimeter of the grounds.” Later on, the cabin was moved to an indoor exhibit.

In March of 1991, Harvey Carr told me about how Rondeau’s cabin was brought out of the woods and became part of the Adirondack Museum’s collection:

We [the logging crew] went into Cold River in the fall of 1958. I was working for Paul Crofut, the logging contractor, who was working for the Northern Lumber Company. The US Bobbin and Shuttle Company owned the property – they’re the company that made wooden spools and such.

We stayed in there during the winter at the lumber camp. We cut the hardwood and brought it out and sometime during the late winter or going toward spring, somebody from the US Shuttle and Bobbin Company came into camp and told us, before we got down toward Rondeau’s camp, they wanted us to take the dozer down, smash it up, bury it and get rid of all the lumber and everything because they were afraid of hunters moving in and causing a forest fire. Of course, that wasn’t a bad idea, but you know, there was brush and weeds and a lot of slash… Anyway, they wanted us to destroy it completely.

I sat there in the logging camp that night and said to the boys, ‘I hate to see it go…Gee, it’s too bad. It should be in a museum or something.’ Then I hadn’t even thought about it for two, three, four days and then I got to talking about it again. You know, like it would be a shame to tear it all apart, bury it and everything. And about then, Jack Swancott, one of the truck drivers, gave me the idea. Real casual like he says, ‘Well you got a museum right there in Blue Mountain Lake.’

I said, ‘Oh yeah, but I don’t know if they’d be at all interested or not. Naw, I doubt they’d want it.’

Jacky said, ‘Well maybe they would.’

‘Course we stayed in there [at the lumber camp] all week and it would come and go on my mind. So…I stopped up there [at the museum]. Oh, it was late January or February ’59.

I mentioned how I felt to Monty and Eleanor [Webb]. They liked that sort of thing – old stuff, antiques and all. I also went up there [to the museum] and stopped to talk to Ralph Raymond. Ralph was the custodian up there. He lives up there year-round and takes care of the place. I explained all about Rondeau’s camp and so forth but he didn’t get too enthused about it. He didn’t know much about it, but I remember Ralph saying to me, ‘You ought to talk to Dr. Inverarity.’

Sometime soon afterward I told Eleanor and Monty about the old hermit camp, and later I took them into Cold River. We drove up in my truck. We stopped at the lumber camp, ate lunch…[and talked about Rondeau]. Monty said they’d talk to Dr. Inverarity. It wasn’t long after Monty, Eleanor, Mary [Carr’s wife] and I had returned home from Cold River that we were sitting eating supper, and right along I got a telephone call from the operator saying this was a person-to-person call from Dr. Inverarity in New York City. He had heard from Ralph and the Webbs. He said, ‘I hear there is a possibility that we could get Noah John Rondeau’s camp. By all means, we’d like it if you can get it out.’

He even talked of sending a helicopter crew up there with some carpenters who could build a framework around it and airlift it from there to the museum. Knowing the camp’s condition and the woods and so on, I knew what I wanted to do. You know they were even going to send a television crew and all that stuff and it was going to be getting late [in the season]…

I didn’t think Rondeau would care too much about that idea. Of course, he had no legal hold on anything back there anyway, but morally it was still his camp. I told Inverarity that if he wants it, we’ll bring it out. ‘What I’ll do is take it apart piece by piece. I’ll number every part and put it back together exactly the way it was and it will be about the same camp.’

I know when I mentioned it to Dr. Inverarity, he sounded excited, just like a kid after you offer ’em some candy. He was tickled to death.

I’d been a lumberjack, not a carpenter, but I knew I was going to do it my way. So, I brought it out, all by myself along with an old iron stove, some cookin’ kettles, a coffee pot, as well as a hollow stump Rondeau had used as a ‘wet sink’ and the only thing I replaced were the bottom logs.

Of course, it’s all inside [now] under temperature control, and its good I suppose for at least for 150 years.

As for Rondeau, nothing ever pleased him as completely or humbled him as sincerely as being honored by the Adirondack Museum’s Cold River hermit exhibit. That seems clear in this letter to Dr. C.V. Latimer Sr.: “Yes, my Cold River City, is a shrine at Adirondack Museum at Blue Mountain and I am more proud of it than I would be of all the shrines of Traitorous H.S.T. [President Harry S. Truman] and Dexter White on top of it.” Now, more than half a century after logger Carr’s effort to preserve what he felt needed protecting, Rondeau’s exhibit has continued to intrigue museum visitors. Thanks to an Adirondack logger, people can still learn about the Adirondack hermit.