Dr. Silas Conrad Kimm lived his entire life in northern Herkimer County, New York. He enjoyed writing about people and times in his life.

A Look Back In Time

Eyewitness to Logging

An article printed in “The Northern Logger “, August 2022

The desire to tell what we have seen is as old as humanity. Dr. Silas Conrad Kimm (1863-1957) was born, raised and lived his entire life in northern Herkimer County, New York. He enjoyed writing about people and about the times in his life. Over the years he amassed hundreds of columns on all sorts of subjects, many of which had to do with his young life working in lumber camps. In 2014, his grandson, Gilbert H. Jordan II compiled the columns into a self-published book, which provides a lot of insight into the big timber days of New York. “The Lumberjack” (undated) is Kimm’s heartfelt tribute to those in the profession.

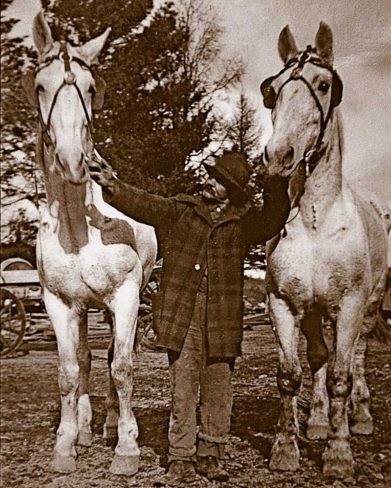

Above: Work horses skidded as many as 200 logs a day. It may be readily understood, therefore, that this was not an easy day’s work for man or beast.

COURTESY GEORGE SHAUGHNESSY

Kimm recounted one by one how the drop in lumber profits finished off small logging towns in Herkimer County. The blacksmith shop, the store, the post office, and finally the school all disappeared. Market conditions made it difficult to dispose of the lumber. Since the nearby forest was cut away, it became necessary to go farther and farther back into the woods to secure logs. The cost of transporting lumber was a big factor in reducing the profits. So many team loads of lumber, even though they were small, made the dirt roads almost impassible in the summer. In the winter, outside of the woods, huge snowbanks, blocked the highways.

The drop in lumber profits finished off numerous North Country logging towns that had come into being only because of logging operations. Hard times led to the timber theft of fiddle butts. Fiddle butts are the finest clear butt logs of Adirondack black spruce. They were once the principal supply for the manufacture of boards for pianos. Kimm writes, “When a man could get as much or more for a single log than for a team lead of ordinary lumber, the temptation to hunt for such logs was great, and he hunted for them without regard to ownership.” A January 10, 1889 Rome Daily Sentinel article, “Thieves Cut Down Forest Trees,” also tells how the state’s forest commission received almost daily reports that the best spruce trees were being cut down. In 1889 butts were “worth $25 a thousand feet in the log.” Fiddle butt timber has a fine straight grain, free from knots. “They are sawed into boards five-eighths of an inch thick. This is planed down to half an inch and made into sounding boards for pianos…the chief forest warden has been actively engaged in endeavoring to catch these depredators …”

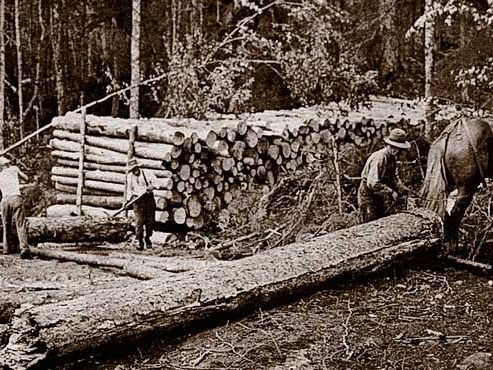

A typical men-at-work-in-the-woods scene.

COURTESY ED FYNMORE

Reading about this history inspired me to reflect on the demand for wood throughout the history of America and the world. Forests have long supplied wood for a myriad of products. Wood has played an important role in the history of civilization. Humans have used it for fuel, building materials, furniture, paper, tools, weapons, and more. Demand for wood has not diminished, and, if anything, people have grown more appreciative of fine wood. Our relationship to this natural resource has remained comparatively unchanged over time, and methods of developing and managing woodlands have evolved into some of the best management practices to naturally renew and replenish millions of acres, while ensuring future generations will have the wood they need for products and the forests they need for recreation. Look around you. You’ll see wood everywhere. So perhaps this is why we take it for granted. Wood will always be a part of our lives despite the prevalence of plastic (which, unlike wood and wood products, takes forever to break down). We are dependent on forest products in so many ways, and we probably can’t imagine our lives without them.

If you’re looking for a good book that covers some of the interesting history, check out the work of Silas Conrad Kimm.

Heavy rains plagued the river drive and sapped ‘jacks’ energy levels, but through it all the whitewater, ice, rain and log jams, the logs eventually reached the mill pond.

COURTESY LYONS FALLS HISTORY ASSOCIATION