Ministers who traveled from one lumber camp to another were called “sky pilots”. Their mission was to pilot lumberjacks heavenward.

A Look Back In Time

Woodsmen’s Sky Pilot Pastors

An article printed in “The Northern Logger “, May 2022

I recently went on a memory trip over rutted roads and mountain trails to meet sky pilot pastor Herman M. Jansson and to see his “parish” of 1,000 woodsmen in 1953. This adventure was made possible by Karl G. Karsch, a writer and photographer who wrote a story that appeared in the October 31,1953 edition of Presbyterian Life magazine, under the title “Woodsmen’s Pastor.” My thanks to the Presbyterian Historical Society for giving me access to this important archive.

Why were ministers who traveled from one lumber camp to another called “sky pilots”? They certainly didn’t arrive in camp by plane or helicopter. Their mission was to “pilot” lumberjacks in a spiritually heavenward direction. The term “sky pilot” is more focused, deeply thought-provoking and easily understood by reading a few lines Rev. Frank A. Reed asked loggers to ponder at one of his deep-woods logging camp services in the southwestern part of the Adirondack Mountains.

In a forest clearing, Herman M. Janssen (right) stops to talk with a husky lumberjack who holds a gasoline-powered chain saw.

Keep us, O God. From all complaining and self-pity. When our work is hard, give us the strength we need to do our best.

When our hearts are heavy,

give us a sense of Thy many blessings now and always. May our efforts and our hopes make us cheerful and serene That others may take new vigor and joy from us.—Amen

Rev. Reed was an Adirondack sky pilot – a preacher who traveled from logging camp to logging camp either on foot, on snowshoes or by riding on whatever means he could find thirty years earlier than Herman Janssen.

Carl G. Karsch introduces us to another woodsmen’s pastor. From Karsch’s article:

“At forty-six, few men would have made Herman Janssen’s decision. A year ago last summer he traded a comfortable parish in Michigan for a “congregation” of 1,000 lumberjacks in the Adirondack Mountains of New York State. He sees his wife and two teen-age daughters only on weekends when he returns home to Saranac Lake. During the week he hikes or drives from camp to camp distributing portions of Scripture, holding informal services, and showing films. Lumberjacks, traditionally untalkative with strangers, are essentially lonely men, Herman says. If he can get a conversation started with a woodsman, Herman feels he can eventually gain the man’s confidence. And once a lumberjack realizes he has found a friend, it is not long before Herman tells him God is a companion, too.”

The point of using dummy text for your paragraph is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution of letters. making it look like readable English.

His Scripture Selections Bring Hope

Before leaving home on Monday morning, Herman replenishes his stock of religious literature and Scripture portions, which he distributes to lumberjacks. This phase of his work is complicated by the number of language groups, principally French-Canadian, found in the camps. In order for men to read in the language with which they are most familiar, he carries pocket-size Gospels in five languages – English, French, Russian, Polish and German.

En route to camp, he frequently stops at a sawmill along the highway and visits among the workers’ homes scattered in the woods nearby. Families of sawmill workers, like lumberjacks, usually don’t go to church. They feel “town folks” don’t want them to come. Mothers are glad for the Sunday school lesson material he brings for them to read to their children. Gradually, Herman hopes to train some mothers in each sawmill area so they can organize their own Sunday school classes.

On roads better suited to horses than a car, Herman borrows a team and sled to carry his pack and movie equipment to camp.

His Visits Bring Help

Audience in mess hall listens to talk following movie. In the front row is the only woman in camp, wife of the cook.

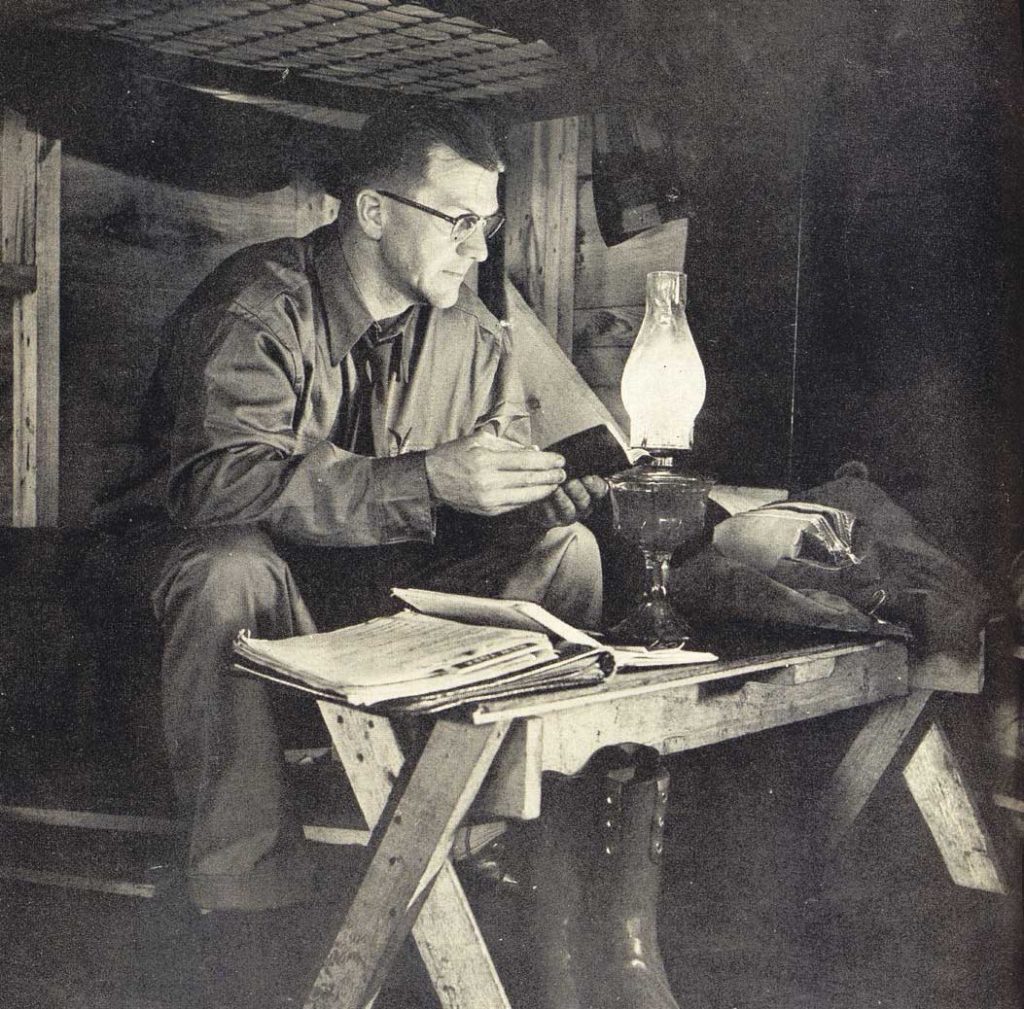

Evenings are the busiest, and the shortest, part of Herman’s day. Into the two hours between the end of dinner and “lights out” (nine o’clock) he must cram a movie, a brief religious talk, and any counseling. He encourages the “bull sessions” that result from the program. More than once they have been concluded over pie left from dinner provided by a beneficent cook. Herman watches for a man who lingers after the meeting, for this indicates he may have a problem to talk over. Personal devotions ended, Herman climbs into a spare bunk. He believes that by staying at the camps the men are more willing to accept him. For the same reason, he wears forest ranger clothes instead of a suit that would mark him as an outsider.

Last year [1952] he drove 14,000 miles between camps, although he walks when the mountain roads are impassable. Into a pack weighing eighty pounds when full go these items: magazines, Gospels, first-aid kits, matches, sheets, and knife. He keeps a compass pinned to his jacket but has never been lost. Herman enjoys the long hikes and has walked as much as twenty miles to a camp. In conversation with lumberjacks who are lonely, Herman points out that he, too, is by himself much of the time, but that in a real sense a man is never alone.

The appeal of all the sky pilots was their knack of imparting a reverence for Christian ideals while respecting the honest toil of hard-working men. They respected and inspired their parishioners while devoting themselves to improving the spiritual welfare of the lumberjacks. The sky pilots were unusual men with an uncanny ability to bring religion and spirituality into the lives of the men they worked so hard to reach. Sky pilots championed loggers in their quest to bring religion not only to New York’s Adirondacks region, but to other states across America’s vast Northern Forest.