They were Adirondack Characters and they all found the region’s history to be as captivating as its varied landscape. Continue Reading Adirondack Characters and Campfire Yarns – Preface

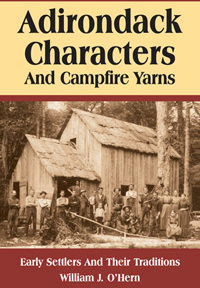

Adirondack Characters And Campfire Yarns

Preface

An excerpt from ” Adirondack Characters And Campfire Yarns “, Starting on page 1

THE SUMMER HIKING and camping crowds leave by Labor Day. The hunting public ends their season. The beautiful forests of the southern Adirondacks become virtually empty, returning to their natural state of quiet simplicity. This is excellent news for people who like solitude.

I favor unconfined recreation. The majority of marked foot trails in the West Canada Creek and Black River headwaters lead to ponds, lakes, rivers, or low mountains. Trails do not lead to the far-removed places I enjoy seeking out. The contest on many of my excursions is to find the locations of former “green-timber” traplines, hunting and fishing shanties built from forest resources, and to identify strategically-placed logging camp sites. Having knowledge of an area’s history gives my adventures greater meaning. Several years ago I reproduced a copy of W. E. Wolcott’s Map of the North Woods by Shady P. Groves, drawn in 1891. It’s one of the many Adirondack artifacts that I have collected over the years. On the reproduction I highlighted the trapline trails that “French” Louie Seymour (1831-1915), the colorful West Canada Lakes character, slogged over. His trails covered territory few modern bushwhackers have ever seen.

I carried that old map on outings into the West Canada Lakes country, not for the scanty navigational information it provided-topographic maps served that purpose-but for the nostalgic feeling of walking in the footsteps of an Adirondack legend. It served that purpose well.

I am a dyed-in-the-wool Adirondack history buff and I’ve spent time most winters traveling, researching, listening to stories and reading about the historic Adirondack destinations that fascinated me the most.

I also collected artifacts. Some are faded, others tinted yellow and brown-toned, dog-eared and fly-specked. Glimpses of bygone days in the Adirondack Mountains stored as they came in a Fanny Farmer chocolate box, a red and white cardboard Royal Medjool pitted dates container, a Peter Schuyler-Victor cigar box, and a vintage Utica Club beer case-no bottles included! Other snapshots were given to me in little stacks tied with old Christmas ribbon, in metal recipe tins and in family scrapbooks. Others came singly. My most prized pictures showed up in a worn manila envelope. It contained just negatives-the old square, thick film variety. They belonged to Lloyd Blankman. His son, Edward, had them stored on an upstairs closet shelf.

Most are snapshots, casual family photographs taken with a hand-held camera without regard to technique. I have no idea who some of the men and women are. Lloyd’s notes identify others.

Twelve are very old professional photographs: thin photographic paper fixed to a thick cardboard backing. One shows French Louie and Truman (Trume) Haskell standing in front of Louie’s camp at Big West. Lloyd wrote on the back: “Taken about 1900. Given to me by Trume Haskell. One of my best and rarest pictures.” Another shows a buckboard bound for Barber’s on Jocks Lake road. One of my favorites is of guide Giles Becraft standing with a party of two “sports” on the shore of Jocks Lake. Dut Barber, owner/ operator of Barber’s Lodge, stands next to his woodsman guide.

Another favorite shows “Red” Jack Conklin and buddies in 1926 at Red’s camp on Gulf Brook back in the woods north of the Haskell Hotel. Hunting success is evident in many of the photos of his camp. That area today is a bushwhacker’s longing.

Those dingy pictures and yellowed journals of bygone days guided me to places where trappers trapped and loggers ran river drives, to one-room school houses and stone fences around the fields of hardscrabble farmers. Many trips to the headwaters of the Black River and West Canada Creek were inspired by stories about the first wealthy sportsmen traveling there by horse and jumper and the guides who led them to the bounty of that pristine wilderness.

Year after year, I collected. Eventually I found that I was depending more and more on materials directly connected to a handful of amateur Adirondack historians: Lloyd Blankman, Rev. A.L. Byron-Curtiss, Harvey L. Dunham, Mortimer Norton, and Thomas C. O’Donnell. They too had spent much of their lives collecting pictures and stories about the backwoods folks of the highland interior. Now I was collecting them.

They were all sportsmen. They loved the Adirondack Mountains, and they all found the region’s history to be as captivating as its varied landscape, as captivating as I find it now.

People who knew them describe men haunted by the chase. They amassed a wealth of woods lore over their lifetimes. Perhaps because the men instinctively knew technological progress would replace the pioneers’ readiness, they made voluminous and amazingly detailed notes to record the skills of survival afield and the ability to live in a harsh climate.

All the men lived during a time when gathering scores of amusing anecdotes and information was painstaking. Many of their subjects were old or had died. The personal histories of natives they sought were already being obscured by the gathering mists of legend and hearsay.

The most important thing to me is that they gathered a supply of sidelights on the nature and texture of mountain life that is factual. Their recordings bring to life the distinctive voices of hermits, moonshiners, gum pickers and anglers with stories of families, feuds and sporting in the North Woods when Adirondack waters were a trout haven.

They wanted people to remember the names of the men they researched, respected and revered. Men like French Louie and Johnny Leaf, the St. Regis Indian who would kill a deer for a pint of whiskey. The bear-teasing Frank Baker, guide for the famed Dut Barber at Jocks Lake, now Honnedaga. Burt Conklin, a local frontier legend. Ferris Lobb, hermit of Piseco Lake. Johnny Jones, Bill Pardy, Roc Conklin, Will Light and other unadulterated “wildcrafters.” These men became some of the best-known characters in the lively headwaters country, because of the numerous newspaper and magazine articles the collectors produced.

Their notes, writings and photos are extremely helpful to me as I plan what I call historical bushwhacks-trips where I make use of the extensive personal papers, diaries, unpublished manuscripts, published articles, and photographs that generous relatives and friends of the men have offered me.

I admired these men for spending a lifetime searching and recording historical information. My adventures were thoroughly enriched because of their interest and research. I realized I should do something with their notes, pictures and out-of-print stories, to continue their work; I just didn’t know what-until an accident brought my thoughts together.

One winter night, as I twirled my swivel chair away from the computer to dart out to the kitchen for a handful of pretzel rods, I tripped over my cat, Rascal, who had curled up underfoot. I fell on the rug, “a double s over tea kettle,” as my grandmother used to say. As I went down, my arms went out to soften the fall, but my aim was misplaced. As I grabbed for the desktop I accidentally knocked over a pile of photographs that included photos from Rev. Byron-Curtiss’ albums and those Edward Blankman had loaned me. Mixed in with scattered vintage images was some correspondence from a 90-year-old occasional pen pal, Walt Hastings.

I cursed as I lay sprawled on the floor. Papers and photos were every- where. The hours I had taken to organize the pictures seemed like a huge loss. As I berated myself for not putting rubber bands around the various stacks, my eyes fixed on a letter from Walt. It was the last letter he ever sent me. I picked it up and began to read. In reminiscing about the history and happenings of the area in question . . . I dug into some old deeds and as far as I can determine, my Granddad arrived on the North Wilmurt scene in 1900, give or take a couple of years, some 30 years after the Reeds . . . arrived to settle at the mill.

I have no idea how long Granddad was at North Wilmurt before he met Addie [Hull].

Addie was a good friend of Granddad’s. [As a result of his infantile paralysis] Addie’s method for get- ting from here to there was by crawling. He wore a pair of hip boots cut off at the feet (so the toes would not catch on roots and rock) and a pair of heavy rubber gloves similar to those worn by power company linemen. With his double barrel shotgun slung beneath his chest he would crawl on all fours, like an animal, to a favorite deer run to watch and wait. Because of his infirmity, balance was a problem and to prevent being toppled over from the “kick” of the gun, he would sit with his back against a tree. After bagging his deer, he would crawl back home to get help to retrieve the carcass. On a visit to his home in 1932, he told me many stories of his life and showed me 28 notches cut on the inside groove of the forepiece of his shotgun, each one representing a deer he had killed.

Walt’s letter went on, but Rascal interrupted my reading as he returned to the room. He now wanted the warm spot under the light. I watched him jump up and settle down. “Lucky cat,” I muttered.

As I fumbled over the photos, now totally out of any sequence or context, I began to look at them in a way I had never seen them before. Walt was still alive and kicking, but Byron-Curtiss and the others were all gone now. The pictures appeared ghostly on the floor, like faces in clouds, a mosaic of vanishing history blowing in the wind.

Instead of reorganizing I found myself randomly reviewing individual items. I focused on details I originally had overlooked. A new order was revealing itself. Pictures were no longer grouped according to whom I had received them from, but by what story they told. Pioneering natives, loggers, stage drivers, guides, well-to-do early camp owners could be categories. So, too, could moms and dads. Barefoot children, posing with rifles, standing by elders. Girls adorned in bows and ruffles with long curly locks, clutching bouquets of ferns. Boys dressed in bib overalls with a single pant strap buttoned at the waistband. Children rowing, carrying packbaskets or riding in them. Proud exhibits of fish hanging from stringers or singly from the ends of makeshift fishing poles. Gangs of loggers posed at their lumber camps. Clothes revealed whether it was warm summer, cool autumn, cold winter or buggy springtime.

For each, I had questions: What became of you, whatever your circumstances? Are any of you still alive? What families still live in the mountains? Do the settings in the pictures still look about the same, or has the landscape so changed that all that remains of those days are the ghosts of those who once roamed the land and the now-silent voices of the people frozen in a moment of time, calling out, “Hurry up and take the picture!”

I handled, sorted and filed one picture. I didn’t have a clue who the little boy in the blue-tinted photo was. I came across his picture in a copy of a 1912 edition of The Life and Adventures of Nat Foster: Trapper and Hunter of the Adirondacks. It had been placed inside the front cover. I believe it is Joseph Byron-Curtiss because his father, Rev. A.L. Byron-Curtiss, wrote the book. Tom Kilborne said it was one of twenty-seven books he inherited when he purchased the Reverend’s camp. A rubber stamp was used to identify where the book was stored. On several pages, a red and blue ink sign reads, “Nat Foster Lodge, North Lake. Adirondacks. P.O. Atwell, N.Y.”

I know the names of the two sporting writers standing on a beaver dam across Fall Stream in Piseco because someone penned the celebrities on the picture postcard. I estimate the picture to be close to a hundred years old, but from personal experience I can attest that paddling that stream is just as chal- lenging now as it would have been when the photo was taken.

Two photos showed interesting portraits of a young Byron-Curtiss and a fishing buddy. Someone scrawled with an old-fashioned pen-the type that required periodic dipping of the steel stylus into a jar of permanent ink- “Row, Row, Row.” Nothing there gives a clue to the person’s identity, but I showed it to one old-timer in Forestport who thinks it might be Ira Watkins, a turn-of-the-century guide who lived in Atwell. I figure there is a good chance he is right. There is also a good chance that every natural setting shown in the photographs could be rediscovered today: The landscape of the headwaters has changed very little in the last one hundred years.

Mortimer Norton once said that outdoorsmen tend to overlook significant features of the North Woods-“its mountain meadows and wild flowers.” Lloyd Blankman would have added, “and the lore of the mountains as well as the Adirondack characters.”

Lloyd’s essays colorfully recreate life in the Adirondack Mountains in firsthand accounts. They contain little formal history, because unlike the works of scholars who sift and arrange facts into understandable sums and patterns, Lloyd’s stories are the stuff of history before it is worked by the hands of historians.

I knew Lloyd had dreamed of organizing his newspaper and magazine arti- cles, along with the published and unpublished works of Harvey Dunham and Mortimer Norton, into a book. It was to be titled “Adirondack Characters,” after the banner of his column in The Courier, Clinton, New York’s hometown newspaper.

A similar book of campfire yarns and Adirondack characters, which would include those authors themselves, was taking shape in my mind. It wasn’t long before I was making further inquiries to find relatives, additional materials, and permission to use them.

In the summer of 2002 I visited Lloyd Blankman’s son Edward and talked with him about the project. I quietly suggested to Ed that I would like to finish his father’s dream, by way of incorporating material I had collected that bore a likeness to stories told by Lloyd. I wanted to produce a book that told the stories of early settlers-stories that originated from the West Canada and Black River headwaters.

Almost immediately Ed replied, “You have my permission to use all the material my father gathered and was given permission to use.” He disappeared into another room, coming back shortly with two boxes containing additional treasures of antiquity.

“You’re tapped into an interest of mine,” he said. “My father enjoyed gathering fresh and authentic material for his lectures. Yes, go ahead. As a matter of fact I would love to write an introduction.”

Funny how things go. If Rascal had not been underfoot, the idea to assemble these early Adirondack folklorists’ anecdotes and photographs into a book might never have crystallized. I’ll say thanks now, Rascal, because I certainly didn’t then.

My other colleagues in the preparation of this book are Lloyd Blankman, Rev. A.L. Byron-Curtiss, Harvey L. Dunham, Thomas C. O’Donnell, and Mortimer Norton. They were all woodsmen at heart, their haunt the south- western Adirondacks. There they fished and hunted, and were “regulars” sharing their lives with the natives of the region. The writers are long deceased, but their stories, articles and memories about a variety of Adiron- dack characters, their vocations and their uniquely Adirondack way of life live on. This book weaves their works together with mine to present a glimpse of Adirondack pioneer life, an artifact that can provide future readers with an appreciation for a plain-spoken way of writing and some good old campfire yarns.

William J. O’Hern, March 2004