1903 Fish Creek Lumber Camp Murder

Published in “Northern Logger” magazine, April 2023

From Viewpoints, “Letters to the Editor,” Hamilton County News, July 1, 1987. From the time the first double-bitted axe bit into a tree to the final river log drive, the century-and-a-half period brought lumber camps to house lumberjacks scattered all over the Adirondack North Country and Tug Hill. Just how many camps there were and their exact locations would probably be only a guess, but the number would easily run in the hundreds.

PHOTO COURTESY EDWARD BLANKMAN (THE LLOYD BLANKMAN COLLECTION

Bert Conklin at the top of his game.

I have bushwhacked high into Cold River country’s Ouluska Pass in the northern Adirondacks hoping to find some remains of a lumber camp Dick Wood and EJ Dailey spoke about during their late 1910s and early 1920s fur-trapping days in Cold River country. The duo spoke about the remains of a small chopper’s shanty in the shadow of Seymour Mountain. A female cook had reportedly died of mysterious circumstances according to the reports learned from men at Lumber Camp 4, a site now occupied by a lean-to approximately a mile beyond Ward Brook lean-to.

At one time there had been a rough tote connection between Camp 4 and Ouluska Pass, but today the terrain between the two points makes for a challenging bushwhack.

Careful investigation today can still reveal leftovers from former lumber camps. Searches generally turn up old bottles – usually liniment, whiskey, and medicine – as well as all types of metal objects. A good many of the old camp clearings and sites I have found have been dug up by bottle collectors and those looking for interesting things from the old logging days.

Cold River lumber enthusiast and historian, Sharp Swan, has spent years combing the High Peaks between Seward, Donaldson, Emmons, and Couchsachraga mountains. His investigations have resulted in a considerable wealth of history of the old logging days in that far-off section. But his hobby, as with other searchers, more than likely has not turned up a majority of the locations of former camps. Evidence of early camps has become harder to find over the passage of time. Once grassy areas, the camp clearings first filled with brambles and pioneer tree species, then by an overgrowth of forest that has completely hidden the sites. Sometimes the bottoms of foundations are spotted where buildings were banked with earth, and the trenches where the banking was dug along the sides of the buildings are often the most evident signs that a camp was there. Even rarer are the remains of an old root cellar.

I find the best stories of old pulpwood camps come from the memories of old-timers. Folklorist and writer Helen Escha Tyler told of a fascinating 1918 pulp job on the slopes of Whiteface Mountain in her Mountain Memories (1974). She based the story in part on an interview with Asa Lawrence of Wilmington, NY. Former Hamilton County historian Ted Aber’s books are also good resources of collected stories and tales.

This memory of B. Harold Chartock of Wilmurt, NY, is an example of a true event that was never documented by Dr. Eliza Jane, the current Hamilton County historian. Like so many logging camps, this camp and everything Mr. Chartock describes exists solely in the following letter he wrote to the Hamilton County News, which published it July 1, 1987.

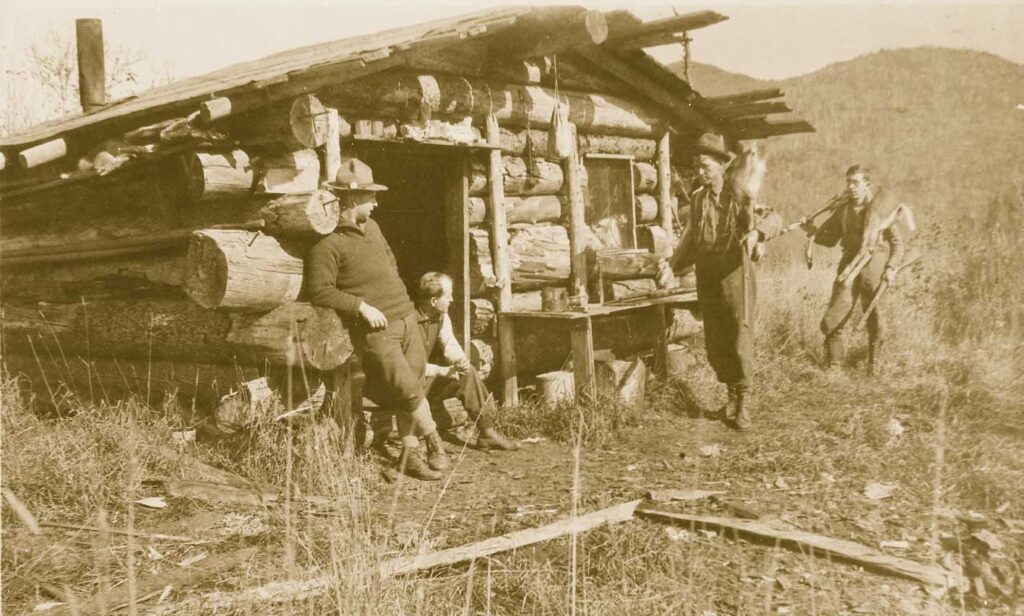

Photo courtesy DICK WOODS

Abandoned lumber camps made ideal ready-made shelter for sportsmen.

Dear Chris:

The Fish Lumber Camp was located on the northeast corner of Round Pond, which is west of King’s Flow about a mile.

One morning Mr. MacKenzie, a lumber-jack from this camp, after crossing the upper Round Pond Brook walking on the Pine Peak Brook-Tannery Bark Road, was entering an old logging field when another lumberjack from the same camp came up behind him and suddenly struck him with a heavy rusty iron wagon bolen in the back of the head, smashing a hole in MacKenzie’s skull.

The killer then dragged the dead body way out on a peninsula that protrudes out into the southern end of Round Pond. He hid dead MacKenzie in a dense spruce and hemlock thicket, surrounded by towering white pines.

This murder occurred in October 1903. About a month later in November, two more lumberjacks from the same camp, one of them George Hutchins of Indian Lake, found MacKenzie’s body. It was badly decayed.

With a shoulder pole, they carried him out to the end of the peninsula and dug a hole, buried him and gathered rocks scattered in the woods, and then heaped up a pile of rocks marking his grave.

Others in this camp noticed after these two lumberjacks came up missing that all of MacKenzie’s belongings remained untouched, but the other missing lumberjack’s things were gone, including a ragged old blanket that belonged to Lowell Fish. MacKenzie’s murderer gathered his belongings, his rifle, and Fish’s blanket then took the Kunjamuk road going around the west side of Round Pond, walked to Speculator, Lake Pleasant, Piseco Lake, Hoffmeister, Morehouse, and Nobleboro. Then he took the West Canada Creek wagon road up to Honnedaga Lake and a foot trail bearing west to a small settlement on North Lake, where he asked for a job.

He was told the Conklin Logging Camp up in the Town of Webb. He arrived there the next day and got hired by Burt as a log cutter to work in his chain of lumber clearings from October 1903 to May 1904.

Burton Conklin noticed that this new guy worked well, didn’t brawl, drink, or court women, and he hid, so none of the visitors to the camp ever saw him. It was in May 1904 that he got the rest of his pay from Burt, which was $5 per week plus food and lodging, but didn’t say he was quitting.

Burt watched him, and later spotted him removing a ragged old blanket from a hollow tree. He got his rifle out, cleaned grease off the metal parts, polished up the woodwork and left the blanket laying on the ground, took his rifle and bundle of stuff, then walked off into the woods never to be seen again by Burt.

It was sometime later that Burt realized this guy’s peculiar behavior was that of a murderer. He notified the sheriff and deputies, and they traced MacKenzie’s murderer to a train station in Utica, where he bought a ticket. State and federal detectives took over and the manhunt was on. They lost his trail after he got off a train out in the state of Colorado. Burt Conklin never heard of Fish’s Camp, nor the MacKenzie murder. He died in 1947, age 84. The MacKenzie murderer left the “Adirondack Rocks” for the “Big West.”

My great-grandfather worked in the Crotched Pond woods back in the early days before moving to Pennsylvania to work with his cousin in leather processing. This murder took place between the existence of New York State Troopers.

They were established in 1860, served just in the cities, got abolished in 1865, and re-established in 1917 to serve only in the countryside. So, 1987 is the 75th anniversary of the New York State Police. Pennsylvania State Troopers were established only once, and that was in 1905, so 1987 is their 82nd anniversary.

The police thought they were after the September 1903 murderer of Mr. Dexter of Franklin County. The two murders are unrelated. The MacKenzie murder of Hamilton County is not a story; it really took place.

—B. HAROLD CHARTOCK, WILMURT, NY

This old newspaper article is fascinating and seems to have all the elements of a good mystery novel set in a lumber camp at the turn of the 20th century. No other mention of this camp has surfaced during the research I’ve done. It’s strange to think of all the buildings and people who have basically vanished from the Adirondack landscape – just like the MacKenzie murderer did, only more slowly and with only Mother Nature to guide the changes.